Antitrust, tariffs, and the "dash for cash"

Here's a hodgepodge of what is on my mind today while I write in my childhood bedroom and listen to mom puttering around downstairs.

On April 10-11, I plan to attend the "2025 Antitrust and Competition Conference - Economic Concentration and the Marketplace of Ideas."

I was fortunate to attend the first conference in 2017, while a JIR fellow, and then the five-year anniversary conference in 2022. I wrote about what changed in between the two and what happened to antitrust enforcement during those years in two stories for the Chicago Booth Review.

Matt Stoller will be at the conference, on a panel on Friday about antitrust and the 1st Amendment. I was chuffed to see not one but two mentions of the accounting industry — both in the bad news section — in his March 31 newsletter:

· The big four accounting giants are colluding to attack the IRS’s goal of getting Coca Cola to pay taxes.

· The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants is seeking feedback on ethics as it relates to increasing private equity investment in accounting firms. Any thoughts?

On the former issue of auditors helping audit clients evade tax, I have written extensively.

In the last piece I talked about my long relationship with Coca-Cola, especially with regard to nostalgia for Mexican Coke, the drink not the drug.

When I was working in Latin America, in particular Mexico, for KPMG Consulting then BearingPoint in the late 90's and early 2000's, a "Cuba Libre" was my cocktail of choice when I was not drinking tequila. Coca-Cola Femsa was my client. We were building a digital marketplace for them with Ariba software, then independent, now part of SAP.

What's great about Mexican Coca-Cola is that it is made with cane sugar, not high fructose corn syrup, a bit of native protectionism of the Mexican corn farmers. As a result, it is the sweetest thing!

With regard to the AICPA seeking comments about auditor independence and private equity, well, this is what I said to Matt on LinkedIn:

Funny thing is that Nobel Prize-winning economist and former NYT columnist Paul Krugman has also talked how how sweet it is, Mexican Coke that is, when providing a primer on all the ways countries can implement protectionist trade policies.

Tariffs are not the only thing!

To understand why the RTAA was necessary, start with the fact that many people say that Coca-Cola made in Mexico tastes better than Coca-Cola made in the United States. (As a black coffee guy, I have no personal view.) Why? The immediate answer is that Mexican Coke is sweetened with cane sugar, while U.S. Coke is sweetened with high-fructose corn syrup.

Behind this difference, however, lies trade policy. U.S. imports of sugar are limited by an import quota, which has effects similar to those of a tariff. As a result, raw sugar is considerably more expensive in the U.S. than it is in the rest of the world and using high-fructose corn syrup is a cheaper alternative:

I highly recommend these two excellent Krugman explainers if you are trying to understand all the fuss about tariffs on and tariffs off.

Feb 16, 2025 and April 5, 2025

In honor of the Stigler Center Antitrust and Competition Conference, allow me to comment on a couple more Matt Stoller missives. First, this very Chicago-focused one reported in his Big newsletter on March 10:

Walgreens, after being driven out of profitability by dominant PBMs, is being taken over by private equity firm Sycamore Partners. It is now planning to close 1,200 of its 8,500 locations.

Did no one but Crain's Chicago Business, where Walgreens is headquartered, mention that Walgreens has a Senior Advisor for Sycamore Partners on its board, and that John Lederer — who has been on the board since 2017 — and Executive Chairman Stefano Pessina recused themselves from the vote on the go-private transaction?

Walgreens' board of directors unanimously approved the transaction, but Executive Chairman Stefano Pessina and Sycamore Senior Advisor John Lederer were recused from the deliberations and approval, Walgreens said.

Both Sycamore and Walgreens have entered into voting and reinvestment agreements with Pessina, who owns 17% of Walgreens shares. Under the agreement, Pessina will vote all his shares in favor of the transaction and reinvest all cash received in the transaction, ultimately maintaining his stake in the company, according to Walgreens.

The Chicago Tribune's Vintage Chicago newsletter — which I subscribe to — is where you can read all about Walgreens historic roots in Chicago and look at some cool photos like the one above.

Charles Rudolph Walgreen Sr., son of Swedish immigrants, moved here from Dixon, Illinois, just as people from around the globe arrived for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Walgreen struggled, however, to keep a job that excited him. It took a near-death experience in Cuba while fighting with the Illinois National Guard for Walgreen to pursue a slower pace of life.

What Walgreen found at 4134 Cottage Grove Ave., on the first floor of The Barrett Hotel, was a shabby, dimly lit apothecary owned by Isaac W. Blood. Though poorly stocked and short of customers, Walgreen realized the South Side store’s potential. Through hard work and innovation, the 20-something saved up enough money to buy a partnership in the business. For a while it was known as Blood-Walgreen before Walgreen bought it outright and had the name “C.R. Walgreen, R.Ph.” placed in gold letters above the store’s entrance. The year was 1901 and the establishment became the very first Walgreens location.

Become a Tribune subscriber: It’s just $12 for a 1-year digital subscription

Subscribe to the free Vintage Chicago Tribune newsletter, join our Chicagoland history Facebook group, stay current with Today in Chicago History and follow us on Instagram for more from Chicago’s past.

Here's two more:

Here’s another story I saw in Stoller’s Big.

Shortly after the results of the U.S. Presidential election were in, Omnicom Group announced it would buy ad agency holding company Interpublic Group (IPG) for $13.25 billion. This deal would shrink the “Big Four” agency companies to just three.

Which Big 4 global audit firm audits each of the Big 4 ad agencies?

In some industries the market concentration of the Big 4 public accounting firms has cured previous allergies to the same firm auditing competitors — see JP Morgan and Bank of America both audited by PwC, Wells Fargo and Citigroup both audited by KPMG, Cigna and Humana (PwC), and First Data and Equifax both audited by EY in Atlanta by the same partner.

The Big 4 advertising agencies, however, are still shy about giving any audit firm access to proprietary competitive information that can be shared with a competitor who is also an audit client. Omnicom is audited by KPMG, WPP by Deloitte, Interpublic by PwC, and Publicis by EY and Mazars.

So, if Omnicom buys Interpublic who loses a client? Likely target auditor PwC is the loser. PwC has been with this client since 1952.

Fees lost? For 2024 total fees were $26.6 million, but fees over the last 25 years were nearly $1 billion.

Finally, there's a lot of talk today about how, in Paul Krugman's view, there are "growing signs that we’re at risk of a tariff-induced financial crisis." Krugman mentions Austan Goolsbee, another "Friend of Chicago Booth" who's now head of the Chicago Fed.

Here I am sitting in Goolsbee's Booth office in his old boss's chair.

Via Krugman today:

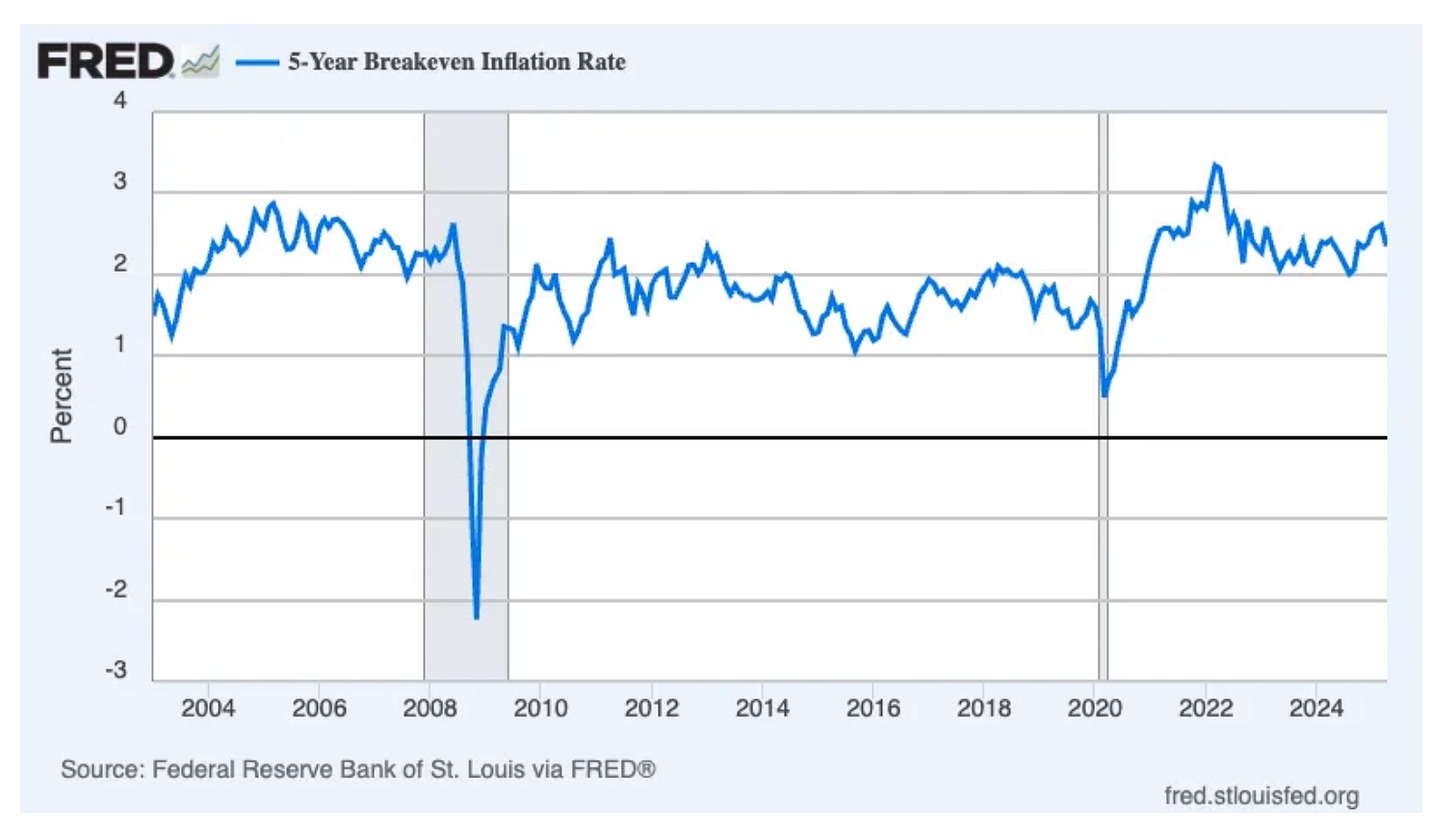

Late last month Austan Goolsbee, president of the Chicago Fed, said that it would be a “major red flag of concern” if market-based measures of expected inflation rose. He mainly meant “breakeven” rates, the spread between interest rates on bonds that are indexed to consumer prices and bonds that aren’t. That spread can normally be seen as an implicit prediction of how much consumer prices will rise.

So here’s the 5-year breakeven rate this year:

Wait, what? Has expected inflation actually fallen as Trump’s tariff plans have proved far more aggressive than anyone expected?

No, that’s not what’s happening. What we’re actually seeing is investors, especially hedge funds, selling assets in a “dash for cash.” When investors sell off bonds, they drive their price down, which means that they push their yield up. Why does this cause the breakeven rate to fall? Because the market for indexed bonds is relatively small and thin, so the rush to sell has a bigger effect in depressing prices and raising interest rates for index bonds than for ordinary bonds.

This isn’t the first time this has happened. Look at the breakeven rate over the long term: It plunged during the 2008-9 financial crisis and again when Covid hit:

Investors weren’t really predicting huge deflation in 2008-9, they were just rushing to sell assets and raise cash. And that’s what’s happening now, although not to the same degree (yet).

In other words, I was looking for guidance about inflation and instead found the telltale signs of an incipient financial crisis. Others, looking at other indicators, from the basis trade to junk bonds to struggles to refinance private loans, are seeing the same thing.

Why is this happening? Trump’s erratic policies have increased the risk of recession, but besides that their sheer extremism — from almost-free trade to tariffs higher than Smoot-Hawley in less than three months — has hurt some borrowers much more than others. Look at the chart at the top of this post. There’s a reason Elon Musk is lashing out at Peter Navarro, Trump’s tariff guru, calling him “Peter Retarrdo” and declaring that he is a “moron” and “dumber than a sack of bricks.”

I wrote about this “dash for cash” scenario for Chicago Booth Review when it happened during Covid.

The intraday liquidity requirements imposed after the financial crisis changed this dynamic, the researchers explain, by tying banks’ ability to lend in the repo market during periods of stress to the quantity of reserves they hold. When a funding shock reduces the available reserves relative to the demand for repos from shadow banks, banks’ lending capacities are constrained and repo rates can spike. If the shock is severe enough and expected to last, shadow banks may respond by liquidating part of their Treasury portfolios to avoid paying high repo rates over an extended period.

This framework explains what happened in the US Treasury market in September 2019 and March 2020, the researchers write. The September 2019 disruption was driven by a tax deadline and was, therefore, perceived to be temporary. It drove repo rates above the interest paid on reserves, reflecting a scarcity of repo supply. Because shadow banks were expecting markets to calm down quickly, they preferred to pay a high repo rate for a short period of time rather than liquidate their Treasury portfolio. In contrast, in 2020, Treasury yields rose sharply while repo rates didn’t. Challenges associated with the pandemic were anticipated to be longer-lasting, so shadow banks, faced with potentially paying high repo rates for a while, dumped Treasuries and cut their losses.

The researchers write that their model helps identify the conditions that lead to repo-rate spikes, and sheds light on the role a central bank’s balance sheet plays in transmitting funding shocks to the Treasury market. US government debt has grown dramatically over the past two decades, and so have Treasury securities outstanding on the Fed’s balance sheet. A larger central-bank balance sheet, combined with an increased supply of reserves on commercial-bank balance sheets, encourages commercial banks to lend more in the repo market following a liquidity shock. A reduction in the size of the central-bank balance sheet exerts simultaneous pressure on both the demand and supply of repos, increasing the likelihood of disruptions, the researchers conclude.

© Francine McKenna, The Digging Company LLC, 2025