Auditors as whistleblowers: When it does, and does not, happen

Recent news reports and a blockbuster legal exposé from a veteran EY partner got me thinking: Is it possible there are more public accounting firm whistleblowers out there?

“In a room where people unanimously maintain a conspiracy of silence, one word of truth sounds like a pistol shot.”

― Czesław Miłosz, Polish-American poet, prose writer, translator, and diplomat who won the 1980 Nobel Prize in Literature.

“You own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories. If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should've behaved better.”

― Anne Lamott, Bird by Bird

Bloomberg Law reporter John Holland wrote on July 22 that the new Paul Atkins-led SEC has been rejecting Dodd-Frank whistleblower claims at a "record" pace.

The SEC is denying a record percentage of whistleblower claims, including two in orders that sharply rebuked a previous award to activist investor Carson Block—signs the agency is enforcing rules and scrutinizing claims more strictly than in past years.

The commission, now with a Republican majority, denied awards in 31 consecutive orders issued between April 21 and July 15 – covering at least 55 different tipsters, Bloomberg Law found in a review of all 65 final orders issued this year. It’s the longest drought in the history of the program, which was created by the Dodd-Frank law of 2010 to encourage tips about financial wrongdoing.

Approximately $20 million has been awarded so far this year, including three awards totaling about $9 million that the agency made on July 16, two days after Bloomberg Law asked it about the lack of approvals.

Last year at this time, more than $60 million had been awarded, on the way to $255 million for the year. So far this year, the agency has approved about 13% of all claims, compared to about 37% last year through the end of July.

Is it really a "record" pace of denials? Stay tuned because I went back a ways to see if this had happened before.

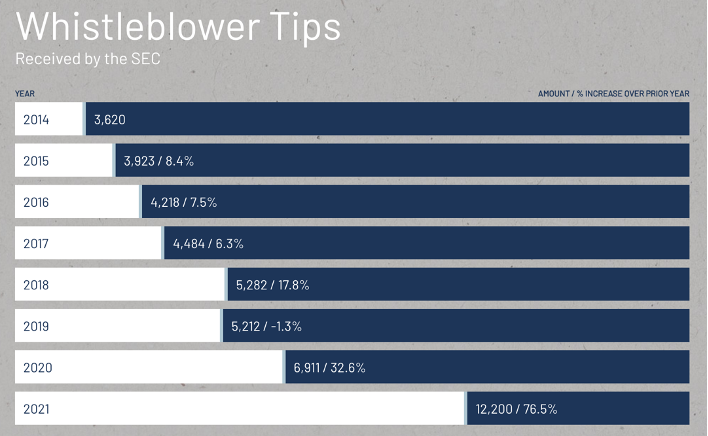

The SEC Dodd-Frank Whistleblower program has grown dramatically.

Sean McKessy, Chief of the SEC’s Whistleblower Office, said that since the program was established in August 2011, about eight tips a day are flowing into the SEC. “The fact that we made the first payment after just one year of operation shows that we are open for business and ready to pay people who bring us good, timely information.”

By 2024 the tips were flooding in, including more bogus and scam tips.

The SEC also received 45,130 tips, complaints, and referrals in fiscal year 2024, the most ever received in one year, including more than 24,000 whistleblower tips, more than 14,000 of which were submitted by two individuals. The SEC issued whistleblower awards totaling $255 million.

It must be said, though, that new SEC Chair Paul Atkins has not been a fan of whistleblower bounties. How do I know?

Yes, that's me, moderating a panel in 2011 with Paul Atkins and Enron's Sherron Watkins and Marion Koenigs.

Mind On The Money: The Dodd-Frank Whistleblower Provisions

Forbes, Francine McKenna Aug 11, 2011

On Friday January 28, 2011, I moderated a briefing for the New York State Society of Certified Public Accountants (CPAs) on the whistleblower provisions of the Dodd-Frank financial services regulatory reform bill. This was a special audience, in my opinion, because it consisted of CPAs and those who support and work with them…

Paul Atkins, former SEC Commissioner, lawyer, and consultant to financial services firms now with his firm Patomak Partners, sees a big problem with the huge bounties the SEC can offer.

Whistleblowers would be able to claim between 10 and 30 percent of the amount collected from companies, but the tip needs to lead to a successful enforcement action by the SEC and the monetary sanction needs to be at least $1 million.

The problem, in Atkin's view, goes beyond the fact the bounties may undercut proceeds to shareholders: They may encourage whistleblowers, and the trial lawyers who advise them, to sit on the fraud and not report it until it grows to an amount that makes the bounty both possible and lucrative.

On July 21, the day before Bloomberg Law's update, former 35-year veteran EY partner Joe Howie dropped a bombshell complaint on the firm, filing a lawsuit in federal court in New York for retaliatory termination related to his whistleblower allegations.

From the 118-page complaint:

37. Investors rely heavily on the global EY organization to faithfully fulfill a vital role: protecting the public interest by acting as auditors of a sizeable portion of the publicly listed and privately held companies globally. The Firm’s public messaging promotes this reliance, with reassuring disclosures about the Firm’s commitments to quality, its robust client vetting processes and controls, and its focus on compliance with professional standards.

For example, in its Transparency Report for the US, EY proclaims, “The consistent stance of EY US is that no client or external relationship is more important than the Firm’s professional reputation and the ethics and integrity of each of our professionals.” EY Global’s stated values include, “People who build relationships based on doing the right thing.”7

38. Yet, the reality at EY is in stark contrast to its messaging. EY leaders have abandoned these stated values and instead prioritized commercial pursuits over meeting their obligations to the public, legal and regulatory compliance, and the quality of EY audits. This has been especially true when those audits involved alleged noncompliance with laws and regulations (“NOCLAR”), including elevated risk of fraud.

7 Transparency Report 2024 - EY US, similar statements are made by the other relevant member firms’ in their Transparency reports or other publications.

It's not yet known if Joe Howie has also filed an SEC Dodd-Frank whistleblower tip, TCR, to report the many allegations of violations of the securities laws that he publicizes in his complaint. He does, however, in his opening paragraphs, claim his activities were "protected whistleblower activities," and that EY's "unlawful retaliation against him, including stripping him of his job roles, terminating his employment and forcing him to take retirement benefits from the Firm early, and the reduction and loss of his compensation" were "in violation of Section 806 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, 18 U.S.C. § 1514A (the “Sarbanes-Oxley Act” or “SOX”).

2. Such activities included, but were not limited to, Plaintiff identifying and communicating matters within EY that involved violations of federal securities laws and improper professional conduct by the Defendants and related EY audit teams.

The word "whistleblower" appears 30 times in Howie's complaint, referring to himself and others — some who have also sued and some who remain anonymous. He identifies several other instances where he says EY whistleblowers were ignored, retaliated against, and forced out, as he says he was.

Some topics and allegations he describes in detail:

EY’s audit client Wirecard, including more on the EY whistleblower that was ignored as well as a fuller picture of the EY US involvement in the Wirecard audit.

The multi-billion dollar fraud at NMC Health

Fraud at U.S. Registrant Luckin Coffee

Fraud allegations and the subsequent charges against the controlling owner of Adani (Listed Company 4).

That "EY leadership across Global, Area, Regional, and member firms—including leaders within Professional Practice Groups—knowingly permitted the Firm to provide audit and other professional services to companies, particularly in the gaming, casino, and hospitality sectors, that were controlled by or closely connected to organized crime syndicates and other criminal groups and activity."

That the "...lead partner on Lehman at the time of its collapse also served in a leadership role in EY’s banking and capital markets group and later was assigned to lead the high-risk audit of Deutsche Bank." (fm note: The two partners on Lehman for EY during the troubles were Bill Schlich and Hillary Hansen.)

That "Ernst and Young LLP and the professionals involved were found to have violated PCAOB standards and they and the Firm were considered a cause of Weatherford’s securities law violations. The lead partner, Craig Fronckiewicz, was barred from appearing or practicing before the SEC. Despite the significant reputational damage caused by Fronckiewicz, EY did not dismiss him for cause. Instead, it allowed him to retire in 2021 – five years after the SEC order."

In March 2021, EY settled a whistleblower retaliation case in the UK brought by former partner Amjad Rihan.

In 2021, EY agreed to pay approximately $10 million to settle SEC charges that it violated auditor independence rules...The SEC order barred one of the lead partners, James Herring, who was found to have engaged in unprofessional conduct, from appearing or practicing before the SEC. Despite the significant reputational damage caused by Herring, after the SEC Order, EY promoted him to be the Americas Value & Growth Leader, a senior markets leadership role responsible for driving the expansion of audit-related services (e.g. cybersecurity, initial public offering readiness) with EY’s audit clients. EY allowed Herring to retire in 2024 – three years after the SEC order and nearly 10 years following his improper professional conduct.

"Despite inquiries from oversight bodies regarding how EY identified and monitored its riskiest audits, the Firm did not disclose and took deliberate steps to conceal the existence and operation of the [Global Watch List] GWL process."

Howie describes "...several high-profile audit failures—such as those identified in the NMC Health trial and recent UK Financial Reporting Council (“FRC”) sanctions—have exposed longstanding independence and rotation violations, rooted in insufficient skepticism and objectivity. In fact, it was recently announced that Shell will amend its regulatory filings with the SEC for 2023 and 2024 due to partner rotation breaches that directly violated U.S. and U.K. independence rules.38These breaches occurred well after Howie and others had raised internal alarms to senior leaders, including Hohl and Huesken."

"Furthermore, whistleblower allegations from former EY tax partner Sayantani Ghose in 2022 had already highlighted red flags related to the Shell audit, including audit team bias and disregard for material tax concerns.39Ultimately, the Shell case underscores EY’s pattern of retaliation against whistleblowers and willful neglect of independence safeguards, resulting in preventable regulatory breaches and reputational harm."

Another partner whistleblower!

273. The ineffectiveness of the program is evidenced by the Firm’s AQR results, which failed to reflect the same level of poor audit quality identified by the PCAOB. Specifically, the gap between EY’s internal AQR failure rates and the much higher PCAOB inspection failure rates highlights that the AQR program has not been effective in identifying audit quality issues...

276. Large gaps also were present between the Global AQR’s minimal failure rates noted and elevated failure rates noted in inspections by the PCAOB. A simple comparison by key country shows Global AQR revealing minimal failures particularly problematic in countries where EY knew it had quality issues, such as China (e.g., AQR shows little compared to a PCAOB failure rate of 75% in the most recent 2023 inspection)...

281. The whistleblower also concluded and reported internally that the severity of the matters rendered EY’s 2024 U.S. AQR program ineffective. They reported broader implications for EY’s overall conclusion of its SQM program, considering the importance of AQR to the evaluation and the senior positions of D’Egidio, Kimpel, Salisbury, Kascmar and others and the other controls and processes they heavily influence.

The whistleblower also noted these matters raised in 2024 indicated the conclusion in the 2023 US AQR program was inappropriate and held implications for SQM.

282. The evidence the whistleblower presented to EY is believed to be comprehensive and irrefutable. Nonetheless, EY responded by attempts at intimidation and retaliation, ultimately forcing the whistleblower's early withdrawal from the partnership under onerous terms, similar to their actions against Howie. Displaying a pattern of behavior that has become common, EY appears to have taken no meaningful actions against the leaders involved in the unethical conduct the whistleblower reported.

Howie's complaint and the Bloomberg report of stricter evaluation by the SEC of whistleblower claims and increased denials made me wonder:

What’s happened to all the Big 4 whistleblowers?

How many just walked away silently or in shame after being retaliated against and terminated?

How many more have sued like Amjad Rihan, Sayantani Ghose, and Howie — and PwC's Mauro Botta?

How many filed SEC Dodd-Frank whistleblower tips, and did any get awards?

How many external auditor and public accounting firm professionals were instead denied because they did not follow the complicated rules for audit and compliance professionals, even more complex than for everyone else?

What are the SEC Whistleblower Tip rules for auditors — internal and external — and other compliance personnel ?

• Rules generally exclude from award-eligibility information obtained in communications subject to attorney-client privilege.

• Rules provide moderate limitations on reporting by non-lawyer compliance / internal audit personnel, as well as directors / officers who receive reports via internal compliance process.

• These personnel may become “whistleblowers” if:

• disclosure is necessary to prevent company from engaging in misconduct likely to cause substantial injury to its financial interests, property, or investors;

• company has impeded investigation of alleged misconduct; or

• at least 120 days have elapsed since the auditor (a) provided the information to the relevant entity’s audit committee, chief legal officer, chief compliance officer (or their equivalents), or supervisor, or (b) received the information, if the auditor received it under circumstances indicating that the entity’s audit committee, chief legal officer, chief compliance officer or supervisor was already aware of the information.

The reason for the 120-day internal notification requirement is to give companies an opportunity to address issues raised by whistleblowers internally. If a company fails to take remedial action to correct a potential violation (and no otherwise eligible individual has blown the whistle first), an auditor can report the information to the SEC and become eligible for an award. Zuckerman Law

Whistleblowing activities are specifically mentioned in at least two of the SEC enforcement actions/settlements involving the largest global audit firms since 2019, the enforcement actions that produced fines and penalties of more than $1 million after 2011, when the SEC's Dodd-Frank Whistleblower Program was established, would theoretically be eligible for whistleblower claims/awards.

And yet, we do not hear much about what happens to auditors and other employees and partners of the global public accounting firms when they blow the whistle — successfully or not.

Let’s look at two of the largest SEC enforcement actions against global public accounting firms — one against KPMG that resulted criminal charges against firm and regulator executives and the other against EY in a record fine against the firm — where whistleblowers are specifically mentioned in detail by the SEC in their settlement documents.

The 2019 KPMG PCAOB date theft and test cheating fine

Although not referred to by name or as a "whistleblower" in the SEC order dated June 17, 2019, we know now that KPMG banking partner Diana Kunz blew the whistle on the KPMG PCAOB regulatory data theft scandal in its third year. From the SEC’s KPMG enforcement action:

Whittle instructed Sweet to warn certain engagement partners about the impending inspections. Though Whittle had warned Sweet to be circumspect in how he communicated this to KPMG colleagues, Sweet’s notice to one KPMG engagement partner caused her to suspect that the firm may have received confidential PCAOB information. These concerns were subsequently reported to the firm’s management, which then reported the matter to the PCAOB, and KPMG began an investigation.

How do we know the “one KPMG engagement partner” was Diana Kunz? Although it was sparsely reported on at the time, her name was eventually revealed during the March 2019 criminal trials of KPMG's David Middendorf and the PCAOB's Jeffrey Wada.

• On February 3, 2017, KPMG National Office partner, and former PCAOB KPMG Inspector Brian Sweet, informed KPMG audit partner Diana Kunz that one of her engagements had been approved for PCAOB inspection.

• Sweet not only explained why the client had been selected but also what the focus areas were for the PCAOB’s upcoming inspection cycle. The audit was still in progress and staff were still conducting fieldwork.

• Kunz contacted her supervisors, John Rodi and Dave Marino, who co-led the Chicago office.

• “It was clear to me that if she was going to be getting notification at that point in time while the audit was ongoing, that we had information in advance that we should not be privy to under any circumstance...Because we would never be notified from a regulator that there was going to be an inspection of an engagement while that engagement was still being executed.” Source: Testimony of David Marino, U.S. vs. Middendorf and Wada 2019, p. 1621

Kunz, and her team, had many choices when confronted with unethical and potentially illegal acts by her colleagues:

• She could have kept quiet, like every other KPMG partner who received advance knowledge of inspections. (I wonder now, though, if there were more reports that were ignored.)

• She could have called the KPMG ethics hotline. (Partners, especially high ranking ones, do not call the hotline. They go to their colleagues, like Joe Howie did, and expect to be listened to, based on their experience and stature.)

• She could have gone to the press. (She has never given an interview. Call me, Diana!)

• She may have called a lawyer.

• She could have gone to a trusted mentor in the firm and confided her concerns. Her chain of command, however, also included someone (i.e., Middendorf) that was a member of “circle of trust” conspiracy.

Diana Kunz, as an experienced lead engagement partner, decided to discuss her concerns with knowledgeable partners that were members of the KPMG National Office and only a few steps below audit practice leadership. Her concerns must have carried significant credibility given her experience, tenure, and knowledge of practice and standards.

As a result, KPMG initiated an internal investigation, reported the issues to the SEC and PCAOB, and the KPMG partners and professionals and one PCAOB professional were charged by the SEC and arrested. All eventually either pled guilty or were found guilty by a jury.

Kunz was not retaliated against, as far as we know. She remains at KPMG and was promoted to lead the Financial Services Audit Practice. The SEC fined KPMG $50 million and she would have been potentially eligible for a reward of 10-30% of that fine. We do not know if Kunz or anyone else involved in the scandal at KPMG or PCAOB filed a whistleblower tip with the SEC. Kunz has never spoken to the press or at a professional conference about her experience, that I know of.

This week I taught our award-winning case on the scandal, “Corruption in the Auditor Inspection Process: The Case of KPMG and the PCAOB”, published by the peer-reviewed journal Issues in Accounting Education, for the third year to University of Michigan MAcc students. I've taught the case multiple times to other programs and each time I ask the question: What is different about Diana Kunz compared to a non-partner whistleblower?

One interesting comment I always get is that partners — for example also EY's Joe Howie — don't use the whistleblower hotlines that all the firms have now. They go directly to their partner colleagues. One reason why may be that, like Sherron Watkins at Enron, they believe leadership will pay attention to their concerns given their experience and stature and they have significant professional and financial incentives not to blow up their firm!

Contrast Diana Kunz's efforts, and her successful result, with what happened when KPMG and the SEC uncovered other unrelated issues at KPMG that, in my opinion, ultimately drove the SEC to fine KPMG. While KPMG was supporting the SEC and Department of Justice investigation of the PCAOB data theft brought forward by Diana Kunz, they ran into another issue that has now plagued several firms, including our fine record-breaker EY: test cheating.

From the SEC's order:

53. On numerous occasions, KPMG audit professionals who had passed training exams sent their answers to colleagues to help them pass those exams. They sent colleagues images of their answers primarily by email or printed their answers and gave them to their colleagues. This conduct was committed by audit professionals at all levels of seniority, including lead audit engagement partners who were responsible for compliance with PCAOB standards in auditing their clients’ financial statements. A number of lead audit engagement partners not only sent exam answers to other partners, but also solicited answers from and sent answers to their subordinates.17

54. Upon learning of the potential cheating, KPMG leadership alerted the Commission staff and began an internal investigation. Soon after, the firm’s Board of Directors formed a Special Committee led by an independent board member to oversee an independent investigation of this conduct. The Special Committee hired an outside law firm to conduct this review. The investigation has revealed extensive sharing of exam answers, with the bulk of this misconduct occurring among junior personnel. While many of those who shared and/or received exam answers engaged in misconduct only once, others sent or received answers to multiple exams.

Prior to the firm’s investigation, no one reported the improper sharing of exam answers to the firm’s Ethics and Compliance Hotline. The firm has been taking disciplinary action against certain partners and other audit professionals in connection with its investigation.

55. After KPMG began to investigate the misconduct, certain now-former audit professionals, including a few lead audit engagement partners, attempted to conceal what they had done.

17 As KPMG itself has recognized, “[t]hose who manage others act as role models.” KPMG Transparency Report (January 2019), available at https://audit.kpmg.us/content/dam/audit/pdfs/2018/2018-transparencyreport1.pdf.

KPMG's Diana Kunz and her National Office colleagues brought the PCAOB data theft activity to the highest levels of KPMG. It was then self-reported to the SEC and PCAOB. On the other hand, according to the SEC, no one had reported the test cheating activity, and even tried to cover it up, even though it went on for much longer and involved many more professionals.

Although the "bulk of the misconduct" occurred among staff, the misconduct was committed by audit professionals at all levels of seniority, including lead audit engagement partners, three of whom were individually sanctioned and subsequently left the firm. In fact, the lead engagement partners in KPMG's test cheating scandal that helped staff cheat did so after their fellow partners were arrested and criminally charged in January 2018 for the PCAOB data theft scandal!

For our recent British Accounting Review published paper on the KPMG PCAOB scandal, we hand-collected data including the affected clients from the three years of lists that KPMG National Office professionals obtained illegally in advance from the PCAOB and engagement and quality assurance partner names — including those that participated in the “stealth” reviews of audit workpapers as a result of the advance inspection notice — from trial transcripts and documents filed in connection with the criminal court case related to the scandal.

As I wrote for MarketWatch:

The KPMG cheating scandal was much more widespread than originally thought Record-tying $50 million fine was expected, but additional details cause experts to wonder if anything will actually change MarketWatch, ByFrancine McKenna June 18, 2019 at 5:03 p.m. ET

For our research we documented hundreds of partners and staff that were involved in planning and reviewing audits and workpapers based on the illegal advance notice of PCAOB inspections, as well as the internal project to have Palantir create a prediction model based on the illegally obtained data from the PCAOB over three years. Were there more KPMG whistleblowers that did not get as far as Diana Kunz?

EY cheating on CPA ethics exams and misleading investigation $100 million fine

When it was announced on June 28, 2022, the SEC said it was the "Largest Penalty Ever Imposed by SEC Against an Audit Firm".

In addition to facts similar to the KPMG case — which involved cheating on internal training exams, including retraining and testing related to remediation for an earlier SEC enforcement action — EY professionals were also caught cheating on CPA ethics exams. Partners at the firm obtained the official answer keys from someone or someones responsible for creating the exam!

And, the most recent time EY professionals cheated on these exams, which began after the KPMG PCAOB data theft scandal was revealed in early 2017, was not the first time. The SEC says in its settled order that there was a "code of silence" about this ongoing and repetitive cheating at EY.

3. Over multiple years, a significant number of EY audit professionals cheated on these exams by using answer keys and sharing them with their colleagues. From 2017 to 2021, 49 EY audit professionals sent and/or received answer keys to CPA ethics exams. In addition, hundreds of other audit professionals cheated on CPE courses, including those addressing CPAs’ ethical obligations. And a significant number of EY professionals who did not cheat themselves, but knew their colleagues were cheating and facilitating cheating, violated the firm’s Code of Conduct by failing to report this misconduct.

4. This sharing of answer keys is not the first time in recent years that a large number of EY audit professionals cheated on exams. From 2012 to 2015, over 200 EY audit professionals across the country exploited a software flaw in EY’s CPE testing platform to pass exams while answering only a low percentage of questions correctly. Following EY’s discovery of that earlier cheating scheme, the firm took disciplinary actions and repeatedly warned its audit professionals not to cheat on exams. Still, the cheating continued.

5. Just as many of its audit professionals failed to report their colleagues’ cheating as required, EY withheld this misconduct from the SEC during an investigation about cheating at the firm.

The SEC says EY leaders lied about awareness of a new whistleblower tip about more violations that was received on the same day the SEC asked about test cheating.

In June 2019, the SEC’s Division of Enforcement sent EY a formal request for information about complaints the firm had received regarding cheating on training exams. On the same day EY received this request, the firm received a tip that an audit professional had shared an answer key to a CPA ethics exam. EY did not disclose this information to the SEC. To the contrary, its submission indicated that the firm did not have any current issues with cheating. In light of the tip it had received, EY’s June 20 submission was materially misleading. But EY never corrected its submission. Even after the firm began an internal investigation, confirmed there had been cheating, and the matter was discussed among senior lawyers at the firm and with members of the firm’s senior management, EY still did not correct its misleading submission.

But EY had received additional whistleblower tips about earlier test cheating violations, too!

8. In December 2014, an internal EY whistleblower reported a flaw in the firm’s software that allowed professionals to pass CPE exams without the required number of correct responses. This vulnerability allowed exam takers to achieve a passing score while answering as little as one question correctly. The firm’s investigation of this matter determined that from 2012 to 2015, over 200 EY audit professionals in multiple offices exploited this flaw to pass CPE exams. (fm note: There is no record of any regulatory action regarding these earlier violations. Were the SEC and PCAOB aware of them at the time?)

10. However, EY learned that, despite these warnings, certain audit personnel were continuing to cheat. For example, in 2016, EY learned that professionals in its Denver office improperly shared answer keys. In response, the office’s managing partner warned staff that these actions constituted a serious violation of the firm’s Code of Conduct and underscored the importance of ethical behavior in connection with CPE. After the firm learned of two employees who had cheated on a CPA ethics exam in 2017, EY issued the following warning to U.S. personnel...

(fm note: According to the SEC EY disclosed the 2017 tip — but not the June 2019 one — in its June 20, 2019 narrative submission to the SEC, provided in response to the SEC’s Division of Enforcement formal request to audit firms including EY asking whether they had received any ethics or whistleblower complaints regarding test cheating. The submission described five matters “related to cheating or other misconduct on training programs and assessments.”)

EY did not disclose a new whistleblower tip, one that had started up the internal chain, on June 19.

16. EY’s June 20 submission created the impression that EY did not have current issues with cheating – either on training programs and assessments or CPA ethics exams. However, on June 19, the day before EY made its submission, an employee reported to a manager that a professional in the firm’s audit group had emailed the employee answers to a CPA ethics exam. That afternoon, the manager informed an EY human resources employee of the tip, which was then relayed to others in EY’s human resources group.

17. Various senior EY attorneys received the SEC Division of Enforcement’s June 19 request. They reviewed EY’s June 20 submission, which conveyed that the firm’s personnel were not cheating on exams. And by no later than June 21, they were apprised of the employee’s June 19 tip about receiving an answer key to a CPA ethics exam.

18. The tip EY’s submission failed to include involved cheating on a CPA ethics exam. It was sufficiently concerning to the firm that it began an extensive investigation. Yet, despite the message from EY’s U.S. Chair and Managing Partner only two days earlier about the importance of integrity and honesty, EY did not correct its submission to the SEC’s Enforcement Division.

Despite what looks like quite a bit of tips made to the EY Whistleblower Hotline and/or to higher level supervisors — it's not clear — the SEC is still quite disappointed about the "code of silence" that appears to be prevalent at EY regarding this type of unethical conduct.

22. Despite the requirement in EY’s Code of Conduct and the firm-wide warnings that audit professionals are obligated to report unethical conduct, a significant number of audit professionals who knew their colleagues were using and sharing answer keys failed to report this misconduct. Many of these EY professionals attributed their silence to a lack of appreciation that sharing exam answers constituted cheating and violated EY’s Code of Conduct, and a desire to avoid getting colleagues in trouble.

These are just two fairly recent examples of egregious violations of ethical conduct by public accounting firm personnel at all levels, including leadership, and significant fines imposed by the SEC. There have been several others, in particular at the Big 4, since 2011 that exceed the $1 million threshold for potential Dodd-Frank whistleblower claims by firm personnel, if they were submitted.

I've done a cursory review of enforcement action press releases for some of the largest audit firms since the Dodd-Frank Whistleblower Program has been in full operation and listed the ones that exceed $1 million in fees. We know that the two largest fines had explicit mentions of whistleblowers. One more, the PwC Sprankle enforcement action, was uncovered, according to my sources, as a result of a report to the SEC by a competing firm.

Given the legally required anonymity granted to whistleblowers by the SEC's Dodd-Frank program at every step, it is virtually impossible, without inside knowledge or publicity by the whistleblowers or their attorneys, to determine whether a specific enforcement action led to a whistleblower claim — successful or otherwise.

I reviewed all of the SEC Whistleblower Claim Awards since 2019, the year of the KPMG PCAOB scandal enforcement action. Since January 2019 through the last order posted on July 22, 2025, there have been approximately 716 total denials of Whistleblower Claims, 32 awards of Whistleblower Claims, and 32 more combination letters that include both denials and awards.

There have been other long stretches of many more denials that awards.

From January 27, 2019 to January 25, 2020, covering the period before and after the June 2019 KPMG enforcement action and $50 million fine was announced, there were 55 Final Orders for Whistleblower Determinations sent out. Only 8 of them were awards and one was both a denial and award. The rest were all denials of claims.

From June 1, 2022 to May 30, 2023, the period covering right before to one year after the EY enforcement action for test cheating and $100 fine there were 140 Final Orders for Whistleblower Determinations sent out. Only 31 were solely award letters, 12 were combinations awards and denials and the rest were pure denials.

Of the successful awards of claims since January of 2019, I found only three that mention that the claimant qualified for the award under the exception for a compliance professional, the additional more strenuous qualification requirements I described earlier. All three of the examples appear to be either industry compliance or internal audit professionals, based on the rest of the language used, rather than external audit professionals.

What does this exception language say?

In reaching this determination, we have considered the application of Exchange Act Rule 21F-4(b)(4)(iii)(B), which excludes information from being credited as the whistleblower’s “independent knowledge” or “independent analysis”—and hence original information2—if the whistleblower “obtained the information because” the whistleblower was “[a]n employee whose principal duties involve compliance or internal audit responsibilities. . . .” 3

Here, the record reflects that Claimant became aware of the potential securities law violations in connection with Claimant’s compliance-related responsibilities. However, an exception applies if

[a]t least 120 days have elapsed since you provided the information to the relevant entity’s audit committee, chief legal officer, chief compliance officer (or their equivalents), or your supervisor, or since you received the information, if you received it under circumstances indicating that the entity’s audit committee, chief legal officer, chief compliance officer (or their equivalents), or your supervisor was already aware of the information.4

Here, Claimant first reported certain of the information to the firm’s Redacted who was also Claimant’s supervisor, and then waited more than 120 days to report the same information to the Commission. The rest of the information that led to the successful action that Claimant reported to the Commission would have been known to Claimant’s supervisor at the time.

Because Claimant satisfies the 120-day exception, the compliance officer exclusion does not apply here to disqualify Claimant’s information from treatment as original information.

2 Under Exchange Act Rule 21F-4(b)(1), “[i]n order for [a] whistleblower submission to be considered original information, it must,” among other requirements, be “[d]erived from[the whistleblower’s] independent knowledge or independent analysis.”

17 C.F.R. § 240.21F-4(b)(1).

3 17 C.F.R. § 240.21F-4(b)(4)(iii)(B).

4 17 C.F.R. § 240.21F-4(b)(4)(v)(C); Order Determining Whistleblower Award Claim, Rel. No. 34-72947 (Aug. 29, 2014) (finding individual who had compliance or internal audit responsibilities eligible for an award because he or she internally reported the information at least 120 days before reporting the information to the Commission).

If I manually review one-by-one all of the denials, all 700+ of them, I may find more compliance/audit exception language. That may provide more evidence that at least some public accounting firm professionals tried to file SEC TCR tips to collect on their whistleblowing, but they failed to jump successfully through the additional hoops for folks in their roles.

The chilling effect of the Mauro Botta case

Coverage of Mauro Botta’s allegations and lawsuit against PwC overlaps some of the same time frame as the KPMG and EY cases where whistleblowers were mentioned by the SEC.

First, from 2015 to 2017, now-former senior members of KPMG’s Audit Quality and Professional Practice group (“AQPP” or “National Office”) – which is responsible for the firm’s system of quality control – improperly obtained and used confidential information belonging to the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (“PCAOB” or “Board”) in an effort to improve the results of the PCAOB’s annual inspections of KPMG audits. The information obtained included lists of the specific audit engagements the PCAOB planned to inspect, the criteria the PCAOB used to select engagements for inspection, and the focus areas of the inspections. The personnel sought the information because the firm had experienced a high rate of audit deficiency findings in prior PCAOB inspections and had made improving its inspection results a priority.

We first heard about Mauro Botta's suit in early 2018:

On March 3, 2018 Mauro Botta, an 18-year veteran of PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP and a former Senior Manager in its Assurance (Audit) practice in its San Jose, Calif., office, sued PwC, alleging that the Big 4 firm had terminated him in retaliation for filing a whistleblower tip to the SEC about audits in which Botta had a reasonable belief that PwC was violating securities laws in the conduct of its audits.

Specifically, Botta alleges his firing was in retaliation for his blowing a whistle on PwC’s conduct on its audit of client Cavium. Botta says his activity is protected from retaliation in accordance with provisions of the Sarbanes Oxley Act of 2002.

Botta was criticized during a trial by judge that took place from February 22 to March 8 via Zoom by PwC’s attorney for referring to some firm partners as “mafia.” An “emotional Italian,” as PwC has referred to Botta, might know one when he sees one.

On the last day of testimony in the case of Botta v. PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, on March 8, PwC’s outside counsel Walter Brown and PwC US and Mexico Managing Partner of Assurance Mark Simon each made damaging admissions that confirm, for me at least, that PwC wants to “have it both ways.” PwC’s declared reason for terminating Botta — “fabricating” a control during an audit — seems to have been a pretext all along. Instead, it seems PwC’s Office of General Counsel orchestrated a plan to retaliate against someone who had violated the Big 4 omertà, which I have been describing for years.

Mauro Botta had finally done the unspeakable after years of being a “character,” as one partner who worked with him testified. Botta was a “character” that PwC put up with because he was, at least, PwC’s character. Botta had gone to the SEC and aired PwC’s dirty laundry, forcing the SEC to open a formal investigation of PwC audits.

"In June 2019, the SEC’s Division of Enforcement sent EY a formal request for information about complaints the firm had received regarding cheating on training exams. On the same day EY received this request, the firm received a tip that an audit professional had shared an answer key to a CPA ethics exam.”

On March 8, 2021, Botta and PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP completed their testimony in the case, Botta v. PricewaterhouseCoopers, LLP (N.D. Cal.) 3:18-cv-02615-AGT.

When Mauro Botta lost his case against PwC, the firm's lawyers really gloated. From PwC attorneys Hueston Hennigan's website:

Mr. Hueston “painted a picture of Botta as a foul-mouthed man unsatisfied with his career, bogged down in conspiracy theories and, at times, out of touch with reality.” Law360 (July 26, 2021)

“PwC LLP was justified in firing a former auditor and didn’t retaliate against him for submitting a whistleblower complaint to the SEC.”—Bloomberg Law (July 26, 2021)

Mr. Botta was a disgruntled employee who—despite claiming to be a whistleblower—committed serious misconduct requiring his termination.”—Bloomberg Law (July 26, 2021)

The SEC enforcement action against EY for its test cheating scandal with the fine that triggered the SEC to request whistleblower award claims was announced June 28, 2022.

The whistleblowers mentioned in the two big cases at KPMG and EY may have been scared off.

Any CPA or public accounting firm tax and advisory professional may be strongly dissuaded from becoming a whistleblower for so many reasons beyond just the way the law makes it harder for them on a practical level.

I asked Jason Zuckerman of Zuckerman Law, who has represented internal and external audit professionals, what else stands in the way of CPAS blowing the whistle:

There are a few factors that might make employees at audit firms less likely to report violations to the SEC:

Many accounting/audit violations do not yield the huge fines required to exceed the $1 million threshhold.

There is apprehension about violating professional duties and company policies. Blowing the whistle entails significant risks, including workplace retaliation, reputational harm, and blacklisting. If a whistleblower is “outed,” it is unlikely that another audit firm or large company would hire them. An award typically will pale in comparison to lifetime earnings at an audit firm, especially if the prospective whistleblower is a partner or in another senior position.

Whistleblowing outside the organization is counter to the prevailing culture at audit firms. There is a culture of conformity in the public accounting firms that discourages whistleblowing. And there is a strong incentive to please clients - to retain them in a hyper-competitive environment and to get referrals to generate new clients. If a client takes an aggressive position on an accounting issue and an employee at an audit firm refuses to adopt that position, that employee might get removed from the account or even fired. The employee certainly will not advance their career by pushing back against the client’s preferred approach.

I have been describing the Big 4 "Code of Silence" for a long time.

There’s a type of Big 4 omertà, the extreme form of loyalty and solidarity in the face of authority usually attributed to the Mafia. Once initiated into firm culture, survival requires adoption of this informal oath of allegiance that makes it shameful to betray even one’s deadliest enemy, your competitors, to legal and regulatory authorities.

Examples of this extreme sense of loyalty to even those who’ve disgraced the profession [but remained loyal to their firm and fellow partners] can be found when partners that have been sanctioned by the SEC, forbidden to audit public companies, are later reinstated by the SEC.

Partners have the resources, professionally and financially, to fight the power. But breaking the "Code of Silence", as PwC Senior Manager Mauro Botta and EY Partners Joe Howie, Amjad Rihan, and Sayantani Ghose have done, is still very, very rare.

© Francine McKenna, The Digging Company LLC, 2025