Banks in disguise: Starbucks, Tesla, Disney and memories

Starbucks may or may not be a good investment anymore but it is surely no longer a place to meet friends, new and old, and that means it is vulnerable to competition worldwide.

On May 24, Marc Rubinstein, who authors the Net Interest newsletter, reminded readers that “even companies that on the face of it aren’t, can be financial companies in disguise.” His writing last week spotlighted five “banks in disguise”: Starbucks, Carnival, Naked Wines, Delta Airlines, and Travel + Leisure Co.

I have written a lot about Starbucks and its gift card racket. You can read Rubinstein's takes on the other four companies. I'll talk a bit more about a few companies that I have written and taught that are not primarily financial institutions but that also function as non-bank banks or not widely-known banks because of their focus on collecting cash upfront: Disney and Tesla.

But first a bit more about Starbucks.

Rubinstein was inspired to write on one of the best known non-bank banks, Starbucks — which according to the popular meme is “a bank dressed up as a coffee shop” — because of Trung Phan's excellent newsletter SatPost. Trung Phan...

...rates the misperception up there alongside “McDonald’s is a real estate company dressed up as a hamburger chain” and “Harvard is a hedge fund dressed up as an institution of higher learning”.

Phan's purpose in writing about Starbucks is to focus on the trend of fewer customers and lower revenue at Starbucks and how Starbucks can bring the customers back. Phan writes that the popularity of the Starbucks Rewards app has dramatically changed the customer experience. That's not all good for Starbucks despite the incredible financial benefits to Starbucks of the growth of the use of the app.

Originally launched in 2001, the reloadable gift card was a popular payment method, but customers were tightening their budgets. To entice customers back, Schultz paired the gift card with a new loyalty program in April 2008: Starbucks Rewards (the first rewards offered were free Wi-Fi and refillable coffees).

In 2010, Starbucks unveiled its Starbucks Card Mobile app, which was usable at 9,000+ US locations. It quickly became America’s largest combined mobile payments and loyalty program. Within a year, 25% of Starbucks transactions were done via the revamped Starbucks Card program.

Starbucks Rewards now has 34 million monthly active members in America and spending on the mobile app has exploded.

In the decade after the gift card launched (2001-2011), customers spent $10 billion total on it. Today, they load or reload $10 billion + per year on the Rewards App (about 1/4th of the chain's entire revenue).

Rubinstein picks up on the role of the Starbucks gift card app in altering the customer experience. What are the financial advantages to Starbucks? Rubinstein writes:

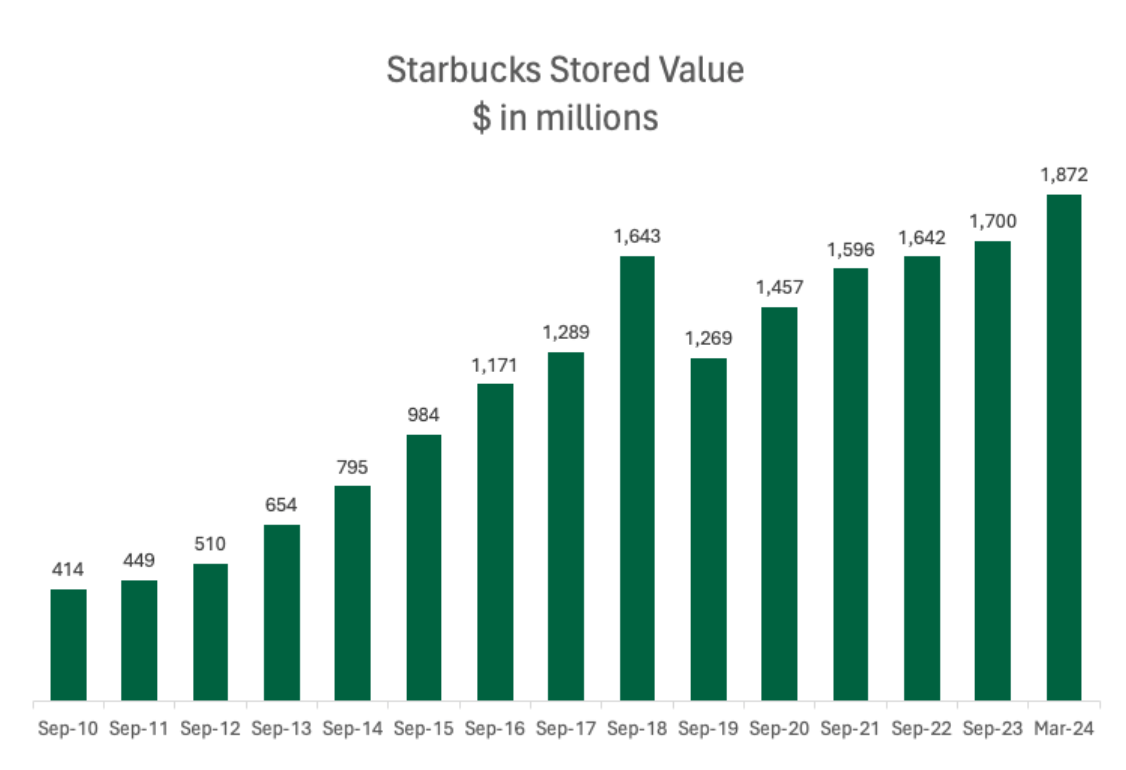

According to Phan, these users load or reload around $10 billion of value onto their cards each year. Turning the coffee shop into a bank is that not all of it gets spent at once. As of the end of March, $1.9 billion of stored card value sat on the company’s balance sheet waiting to be spent – kind of like customer deposits. To give that some context, 85% of US banks have less than $1 billion in assets. And those deposits have enjoyed tremendous growth:

Now, this money isn’t real deposits. The Starbucks card invites you to treat it like cash, but it also says that value stored on it “cannot be redeemed for cash unless required by law.” The only way to cash out of Starbucks balances is to buy coffee.

The issue of gift or "stored value" cards and the tremendous balance sheet impact of "stored value" cards is not new but it’s great that more people are monitoring this quirky component of GAAP revenue recognition rules. (The accounting for the pure loyalty or rewards programs at Starbucks, where frequent purchases earn "stars" for free drinks and food, is different than the stored value cards app. It is a pure liability with mostly cost to company when you redeem stars.)

Stored value in gift cards is accounted for as deferred revenue, and like bank deposits it’s a liability on the balance sheet. That's because Starbucks owes its customers coffee and food items because Starbucks has collected cash from customers in advance for that specific purpose. The key is that only when someone redeems for product can they recognize the revenue. Phan writes:

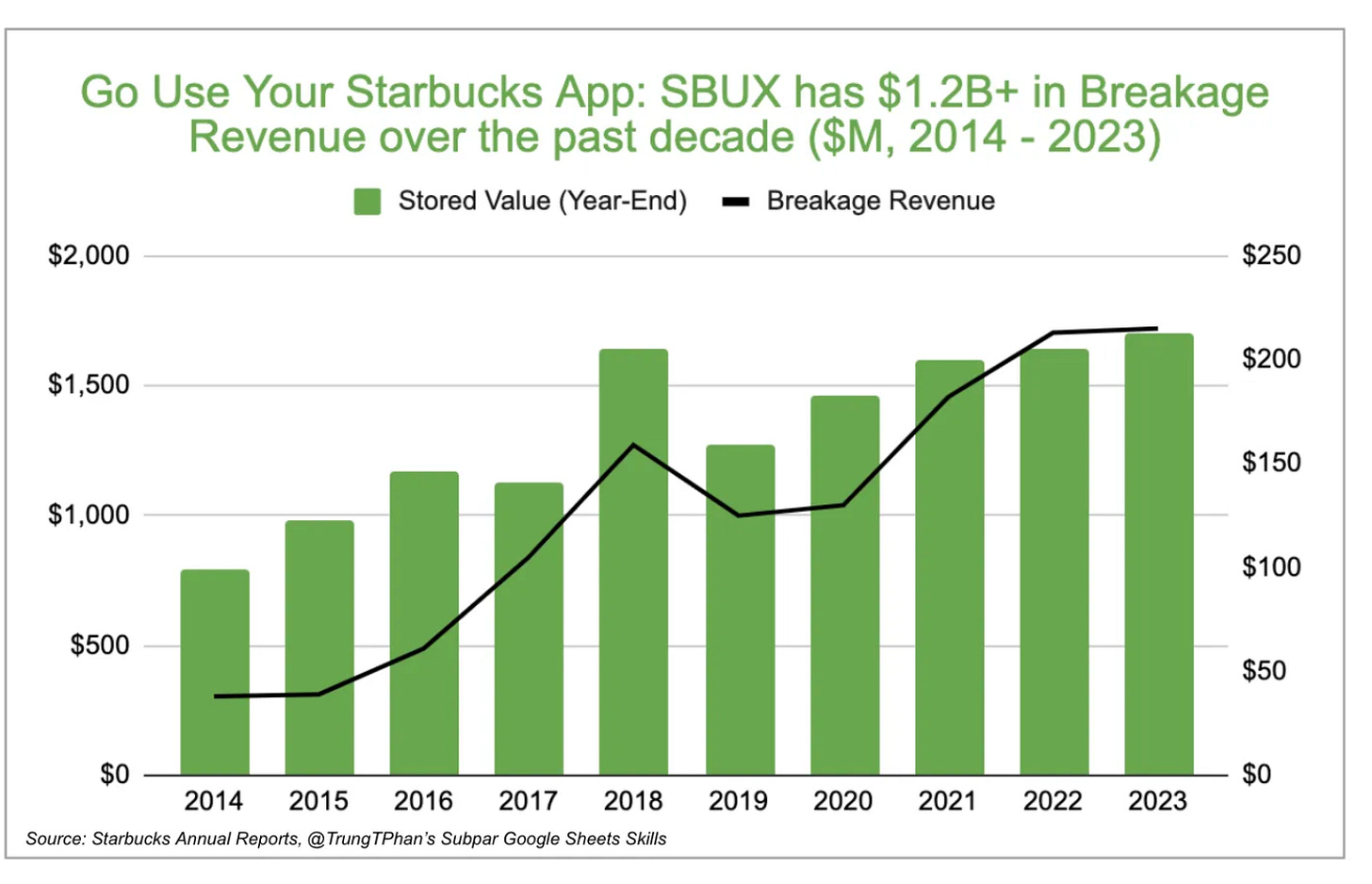

Except for breakage, a strange word for a very positive thing! Breakage is, as Phan writes, a nearly 100% margin benefit for Starbucks that is based on judgment and models and estimates and can be manipulated. Phan writes:

You know those gift cards or loadable consumer apps with like a $3.76 balance that you'll literally never spend? After a certain period, companies get to claim that is revenue. The accounting term for this is called "breakage". There were previously three methods used to estimate breakage, but after changes to accounting rules in 2014, Starbucks now use a method based on historical redemption patterns.

In 2023, Starbucks recorded breakage revenue of $215m. Think about that. The company was effectively paid $215 m to hold $1.7B in customer cards. Wild.

Phan is wrong about when the accounting rules changed, though. It was 2018 not 2014. I wrote about it at MarketWatch in advance of the change.

An obscure accounting change could boost Amazon, Starbucks, Wal-Mart profits by hundreds of millions of dollars June 28, 2017 By Francine McKenna

Gift-card change could result in big bottom-line impact

The new accounting standard is intended to make revenue recognition consistent between U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles and International Financial Reporting Standards. The converged standard, jointly prepared by FASB, which is responsible for GAAP, and the International Accounting Standards Board, which is responsible for IFRS, will change the timing of the recognition of some revenue and may impact the gross amount of revenue presented for certain customer contracts. The new rule requires companies to spread breakage income over the expected gift-card redemption period.

In 2009, Congress passed the Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure (CARD) Act, which prohibited the expiration of gift cards within five years from the date they were activated and generally limits inactivity fees on gift cards except in certain circumstances, such as if there has been no transaction for at least 12 months. In the past, companies recorded a potential liability to customers when gift cards were sold. The liability was reduced and revenue recognized as cards were redeemed. Companies have been recognizing the income impact of gift cards that are never redeemed under multiple scenarios based on their own experience with redemption patterns.

Retailers that currently use five years as the time when the probability of redemption finally becomes remote will see the biggest positive impact from the change. Those that use between 24 and 60 months will still feel the impact of a change to a redemption period that will likely be a year or less. Companies will also feel the positive impact of recognizing the breakage revenue proportionately over their typical redemption period.

You can certainly see how Starbuck has been able to use the new GAAP revenue recognition standards effective in 2018, ASC 606, to its advantage.