Digest: Whether noun or verb, it means there is a lot of news about accounting and audit

Today is a digest of news and views. It might give you in-digestion!

I am back from my whirlwind road trip to the University of Miami and a little bit more time spent with my brothers in Naples, FL. I am the big sister, and they treated me fine, took me to dinner at nice spots, and put up with me for a few days so I could enjoy 85 degrees and sunny instead of 35 degrees and snow in Philadelphia.

Pictured: My Bubbles, The Bad Ass Coffee store at Lowdermilk Beach, and my brother’s Georgia.

There are three classes remaining for my fraud case class at University of Miami. We did two live ones in Coral Gables where students presented the KPMG-PCAOB teaching case I co-authored and also gave up-to-the minute takes on what they think happened at Macy's.

The Macy's case was fun since I asked the students to answer the open-ended question, "What do you think happened?" by only looking at the original November 24-25 reporting, not subsequent filings. They did a spectacular job!

It's at least another month before we have a 10-K for Macy's, so we still don't know what KPMG, its auditor for a million years, will say.

Stay tuned!

On January 31, right before I hit the road for Florida, Ciara Linnane at MarketWatch asked Olga Usvyatsky of the Deep Quarry newsletter and I to comment on a very strange revenue beat by Southwest Airlines.

Southwest Airlines Co. may be at risk of a comment letter from the Securities and Exchange Commission after including adjusted revenue in its fourth-quarter earnings report published early Thursday.

The carrier explained in footnotes that the adjusted revenue, which is a non-GAAP measure, related to flight credits issued to passengers in 2022 and before that. GAAP, or Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, is the standard with which U.S. companies are bound to comply.

Southwest modified its policy that year and decided passengers who had built up credits because they couldn’t fly during the pandemic, or who had points gathered from its loyalty program, could retain those without being subject to an expiration date.

The company had recognized what is called breakage revenue from those flight credits in periods prior to 2024. But based on actual customer redemptions throughout that year and projected future redemptions, it determined it could reverse part of that prior breakage revenue.

The move matters because the $116 million breakage revenue adjustment boosted the revenue number to $7.047 billion, which would put it ahead of the FactSet consensus of $6.959 billion, while the actual revenue number of $6.931 billion represented a miss of the consensus revenue target.

Breakage revenue is a tough concept for most to wrap their heads around and is unique to companies that have gift card, loyalty, and other kinds of customer credit programs. I wrote in 2017 for MarketWatch how several companies would see, for the most part, a big benefit from the new revenue recognition rules effective in 2018.

From the archives (June 2017): An obscure accounting change could boost Amazon, Starbucks, Walmart profits by hundreds of millions of dollars

In this case, Southwest is using non-GAAP metrics to bring back revenue that it had determined — in compliance with GAAP — it should not have recognized in a prior period. The acknowledgement it had overstated revenue in a prior period created a materially negative impact to its top-line, material because it would miss analyst estimates. So, Southwest brought the revenue back, under the cover of non-GAAP metrics, to get the beat.

Olga and I are quoted saying this is a big deal and I think it is likely a violation of SEC rules.

Which one? The one, 100.04, about “individually tailored accounting.” You can’t create a metric to reverse GAAP just because you don’t like the impact.

“Southwest Airlines’ $116 million breakage adjustment is material because it affects revenue and because it leads to a beat,” said Olga Usvyatsky, a former vice president for research at Audit Analytics and author of Deep Quarry, a Substack publication focused on accounting.

The airline broke another SEC rule too, according to Francine McKenna, author of the Dig newsletter on Substack and a former journalist and academic.

“They have adjusted revenue and created their own version of GAAP, a tailor-made accounting metric, which is a no-no,” she said. “The SEC should quickly smack them for both.”

Olga wrote more about this issue, first to further explain what breakage is and then to explain how Southwest compared to its peer group on this issue.

I always like highlighting for the SEC and PCAOB how companies in the same industry with the same auditor sometimes inexplicably differ in their accounting treatment of the same issue.

I noted:

That reminds me of some of my all-time favorite MarketWatch stories about companies' violations of SEC non-GAAP reporting rules, in particular about revenue reporting. While I was there — 2015-2019 — I helped reporters and editors identify these stories and I am gratified to see them continue:

Cigna’s use of adjusted revenue in quarterly earnings does not conform with SEC rules, experts say

Adjusted revenue is one of three metrics used to determine executive compensation

By Ciara Linnane Dec. 21, 2021 at 7:34 a.m. ET

I originally wrote at MarketWatch about Blackberry adjusting revenue, in June 2019, and the company essentially replied, ”You can’t catch us, we're Canadian!”

This turned out to be true, sort of. The SEC did not shut down Blackberry’s abuse of non-GAAP metrics until $BB filed as a U.S. issuer effective March 1, 2020, rather than a foreign private issuer. At that point the SEC’s jurisdiction was unassailable. On March 26, 2021, MarketWatch wrote that Blackberry agreed, after getting a comment letter from the SEC, to stop using adjusted revenue — "ghost revenue" — metrics that take advantage of a “cookie jar” of acquired deferred revenue.

We wrote this next one together while I was still there. It noted that the SEC was following up with comment letters on some of the stories we wrote about.

SEC may be set to crack down on companies that adjust revenue

Some comment letters from the regulator urge companies to stop adjusting revenue, others settle for more disclosure

By Ciara Linnane, Francine McKenna, and Katie Marriner, Nov. 26, 2019

As first reported by MarketWatch in November of 2017, companies were adding back millions in written-off deferred revenue, or “ghost revenue,” when reporting adjusted revenue and when calculating executive bonuses.

MarketWatch had reported on the use of the “ghost revenue” by NortonLifeLock formerly known as Symantec, and by BlackBerry, Salesforce, Broadcom and others.

Read: Companies including Symantec are using ‘ghost revenue’ to calculate bonuses

Still, there are clear examples that the SEC’s interaction by comment letter has led to changes in reporting on revenue adjustments.

For instance, the SEC questioned software company Ribbon Communications in a letter in April of this year about its “acquisition-related revenue” adjustment.

“Considering your deferred revenue was adjusted to fair value at the time of acquisition pursuant to GAAP, please tell us how you considered whether your various non-GAAP measures that include this adjustment are substituting an individually tailored recognition and measurement method for a GAAP measure,” the letter said.

The SEC forbids “individually tailored recognition and measurement” methods because they substitute the company’s own interpretation of accounting standards for GAAP.

Ribbon Communications agreed in a response to the SEC in June to remove the metric from future filings.

Also in April, the SEC took exception to a related adjustment to revenue by BlackRock, Inc., the world’s biggest asset manager. BlackRock was using a non-GAAP adjustment to deduct distribution and servicing costs before arriving at an adjusted revenue metric that it then used to calculate an adjusted operating margin.

“Based on the information provided, we believe your adjustment for distribution and servicing costs in the computation of “revenue used for operating margin measurement” substitutes an individually tailored recognition and measurement method for those of GAAP, which could violate Rule 100(b) of Regulation G,” the SEC wrote.

The SEC told the company not to disclose the metric in future filings.

MarketWatch analysis points to the possibility that a similar SEC focus on adjusted revenue metrics has pushed fintech Square Inc. to take action.

On Nov. 6, Square announced in an SEC filing that it was making a change to its accounting after receiving a comment letter. The company said it would no longer report an adjusted revenue number.

Square said it had been using the metric to adjust gross revenue to net by subtracting transaction-based costs and bitcoin costs. But the company also was adding back deferred revenue that had been permanently written off after an acquisition, the same “ghost revenue” reported on by MarketWatch.

The SEC finally posts Square's comment letter file

The SEC’s scattershot comment letter campaign against measures that “substitute individually tailored recognition and measurement methods for those of GAAP,” is, to say it gently, still a work in progress.

This is the original Symantec story, my all-time favorite.

Companies including Symantec are using ‘ghost revenue’ to calculate bonuses

The SEC and the company are now investigating an employee’s complaint about the practice of adding back millions in deferred revenue to calculate bonuses

By Francine McKenna Published: May 17, 2018 at 6:56 a.m. ET

That one resulted in resulted in FASB changing the rules for how deferred revenue is treated in an acquisition and also resulted in a settlement of the class action lawsuit — initiated by the whistleblow who saw my article — for the plaintiffs against Symantec for $71 million.

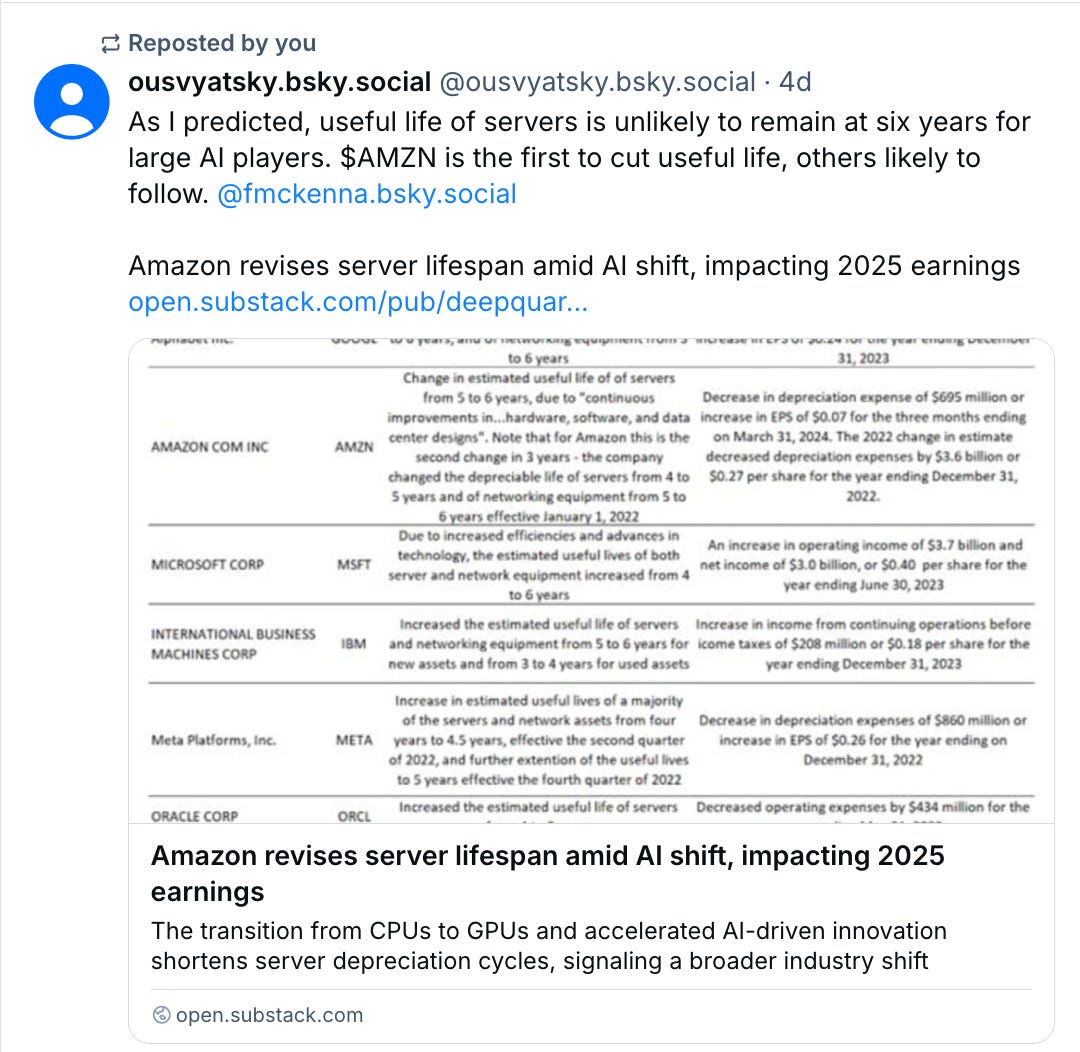

In another 1-2 punch this past week from Olga Usvyatsky and I, Olga wrote about how Amazon adjusted its estimate of its server lives, cutting some lives in its shift from CPUs to GPUs.

A reporter, Jeran Wittenstein at Bloomberg, asked me about Meta's shift in the opposite direction, increasing its useful lives estimates. That's going to boost profits.

Meta isn’t alone in changing its timetable on depreciation — and with it, the financial results. In 2022, Microsoft Corp. extended the useful lives of server and networking equipment to six years from four. In 2023, Oracle Corp. extended its estimate to five years, from four, according to a filing.

Others, however, have taken the opposite approach. Amazon.com Inc. said this month that the lifespan of the equipment is growing shorter — from six years to five. The change, which took effect on Jan. 1, will cut operating income by about $700 million, the company said in a filing.

Unlike real estate, where amortization is spread out over decades, computing and networking gear lose their value much more quickly. The reason is simple: buildings tend to hold their value over long periods; the pace of technology advancement, on the other hand, is so fast that even the most recent models become obsolete in a matter of years, much like an old iPhone.

“It’s the number one number that they can adjust back out because it’s not a cash expense,” said Francine McKenna, an accounting expert and newsletter author. “It’s a big deal in capital intensive companies and in companies that are technologically dependent, where it’s a competitive advantage.”

Finally, behind the paywall, I'll discuss the latest on the fate of the PCAOB, the audit regulator, and why, maybe, it now matters less who independently regulates the auditors than that someone, anyone, enforces the regulations at all.