Disney now on its "goofy foot" in whistleblower lawsuit

After Sandy Kuba defeated Disney's motion to dismiss, both sides have filed motions for a summary judgment in her case of alleged retaliatory termination. There are a trove of new disclosures.

On Friday May 6, 2020, both sides in the case, SANDRA KUBA, Plaintiff, v. DISNEY FINANCIAL SERVICES, LLC, Defendant (6:21-cv-312-JA-LRH) filed motions for summary judgment by the court.

Readers may find background on this case and some of the allegations Kuba raised in my story from August 2019 for MarketWatch:

Disney’s investigation of Sandy Kuba’s allegations should have been focused first and primarily on her concerns about financial accounting and reporting and the potential for fraud. Instead the investigations come across as sham, worse than a reality show called “Real Employees of Mickey Mouse House Accounting”, a knock-down, drag-out, he-said-she said morass of back and forth about people’s tone and demeanor and whether they raised their voice.

Disney executives should have been able, in my opinion, to parse out the interpersonal bickering and ignore the way in which Kuba communicated her allegations.

But they were not.

Sandra Kuba is now seeking an order from the federal court in Orlando:

…granting Plaintiff’s Motion for Partial Summary Judgment as to the liability of Defendant, Disney Financial Services, LLC (“DFS”), on Count I of her Complaint brought under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, 18 U.S.C. § 1514A (“SOX”); (ii) granting Plaintiff’s Motion for Summary Judgment dismissing Defendant’s First, Second, Third, Twelfth, and Thirteenth Affirmative Defenses; and (iii) awarding Plaintiff such other and further relief as the Court deems just and proper.

Kuba’s attorney, Frank Malatesta, wrote that she believes she has established a prima facie case primarily because Kuba says she has met the four elements required to prevail:

To prevail on her SOX whistleblower claim, Kuba must prove by a preponderance of the evidence that: (1) she engaged in protected activity; (2) DFS knew or suspected that she engaged in the protected activity; (3) she suffered an adverse action; and (4) the protected activity was a contributing factor in the adverse action. Johnson v. United States DOL, 814 F. App’x 490, 494 (11th Cir. 2020). If Kuba establishes these four elements, DFS may avoid liability if it can prove “by clear and convincing evidence” that it “would have taken the same unfavorable personnel action in the absence of that protected behavior.” Id.

In a major concession to Kuba’s case, Disney agreed to stipulate that Kuba’s reporting to senior executives in 2016 and 2017 was “protected activity” under the Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank Acts and the company fired her anyway.

From Kuba’s motion:

Here, the Parties entered a Joint Stipulation, which provides, in relevant part, that DFS will not contest that Kuba’s emails dated September 29, 2016 to Kalogridis and dated June 18, 2017 to Kalogridis and Leingang qualify as “protected activity” for purposes of her claims brought under SOX, 18 U.S.C. § 1514A (Count I). Stipulation ¶ 2. As DFS does not contest that most of the June 18, 2017 email to Kalogridis, an executive over parts of Disney’s Parks & Resorts Segment, and Leingang, an investigator designated by Disney to investigate “financial irregularities and control issues,” Kuba has established that she engaged in protected activity under SOX.

As in the Mauro Botta case, why would any corporation choose to make all this dirty laundry public rather than satisfying the yearnings of an earnest long-tenured employee to be heard, and to be treated with respect? Win or lose, there’s no take-backs now.

Disney had knowledge of Kuba’s SOX protected activity but apparently never initiated a full investigation of the most serious financial accounting and reporting concerns Kuba raised.

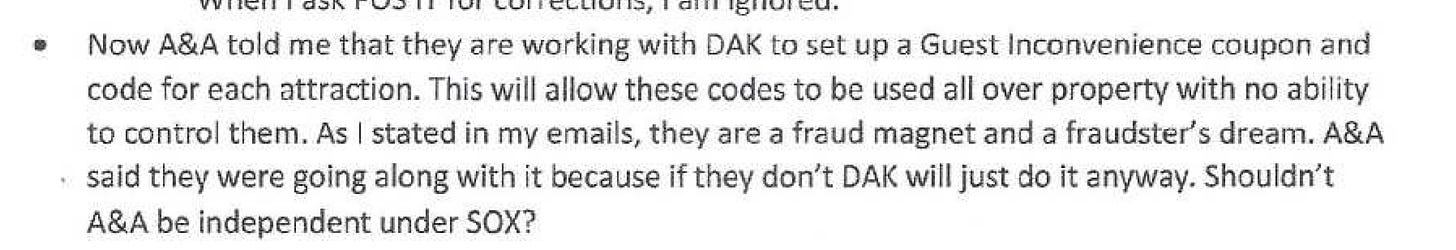

Kuba first sent an email in September 29, 2016 to George Kalogridis, the President of Walt Disney World at the time, raising concerns about potential duplicate or inappropriate revenue recognition transactions, poor internal controls and segregation of duties, and overall environment that could be a “fraud magnet and a fraudster’s dream”. Let’s look at the actual email and the myriad of issues that should have made any executives act immediately to get to the bottom of the allegations from a long-tenured employee who was also in a position based on knowledge, experience and credentials to know what she was talking about. Here’s an excerpt from her email now available in the court docket as Exhibit 1 attached to Disney’s motion.

What did Kalogridis do when he got this email?

He sent it to Tracy Willis, the executive responsible for the accounting functions where Kuba worked and was expressing concerns. If Kuba was concerned that any of her financial or accounting “cast members” were enabling the issues she raised — actively for their own benefit or under pressure from senior executives — Kalogridis failed to protect her and any the integrity of any investigation. He did not address her concerns — concerns about potential revenue fraud and internal control weaknesses. He did not escalate her concerns as “protected activity” that should be given the highest attention and confidential treatment by all involved.

From the Declaration of Tracy Willis (highlight is mine).

In 2016 Tracy Willis, currently the corporate senior controller for Disney based in Los Angeles, was vice president controller for the Parks and Resorts segment based in Orlando. Willis had responsibility for all controllership functions, for all of the accounting activities for the Parks and Resorts segment globally. Willis then forwarded the email to the head of Corporate Management Audit who assigned one of her Directors, Scott Leingang, to begin an investigation.

Who is Scott Leingang? Let’s look at his deposition:

Q What's the name of your current position with Disney Worldwide Services, Inc.?

A Director of Special Reviews within Corporate Management Audit.

Q How long have you held that position?

A Approximately 15 years.

Q Has the duties and responsibilities of that position changed since 2015?

A No.

Leingang testified in his deposition taken by Frank Malatesta, Kuba’s attorney, that there were other directors in Management Audit who could have been assigned the investigation by his boss Helen Davies. Davis was delegated to look into issues from the executive in charge of the activities in question, Tracy Willis, who was alerted by Kalogridis:

Malatesta: So there were three directors of audit and then yourself who is director of special reviews under Ms. Davies?

Leingang: As I recall, correct.

Q Did the other three peers have specific areas or -- of responsibility?

MR. BERRY (Disney lawyer): Calls for speculation.

A Yes.

Q What were those areas, if you recall?

A There would be financial audits and IT audit.

Q Was there another one, or was it just two?

A The two would have the financial audit title and then the one would have the IT audit.

In his deposition Leingang described his responsibilities this way:

Q Can you describe the duties and responsibilities of that position?

A To oversee investigations of financial irregularities of employees within the company and violations of our standards of business conduct policy.

So, despite the fact that Kuba’s allegations related to financial accounting for revenue recognition and internal controls required by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, the head of Disney’s internal audit department myopically assigned the investigation to a director who focuses on individual employee malfeasance not systemic corporate accounting fraud.

(For more about this case, including how Disney’s lawyer gaslighted Kuba during her deposition, you have to be a paid subscriber. Pacer court documents are not free! Use this link for a 25% discount until June 30 in celebration of my new role as a full time professor at Wharton starting July 1.)