Friday round-up: Up next in audit regulation, more cheating, Chinese frauds

It's a dreary Friday in Philly and I've got a whole lot in store for you today and, for paid subscribers, tomorrow.

So many treat me like the bad guy because I am not afraid to speak the unpleasant truth: Getting rid of the PCAOB — which will happen — is only the first step in dismantling audit and financial reporting regulation.

So many have been waiting for just this moment, for alignment of the political stars.

Despite my long and strong support for the PCAOB's mission, for the accounting profession, and for strong internal controls for public companies — it's a career's worth of walking the talk — I am a realist.

The PCAOB is not even officially in the rear view mirror and there are hearings being held to discuss a complete “reassessment" of what's left of Sarbanes-Oxley.

Professor John Coates gave it his best shot but I don’t think it is going to sway this crowd.

Did any of these politicians or corporate governance experts call for Congressional hearings when the Big 4 did not raise a hand to warn investors of the banks and investment firms that soon were forcibly acquired, nationalized and, in many cases bankrupted, during the financial crisis?

Nope. There were none.

The Big 4 global audit firms were mentioned in the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission report — PwC in relation to AIG and EY in relation to Lehman — but no one held hearings to ever ask any of them about their roles the way the UK Parliament did. I wrote:

In March of 2016, "the FCIC revealed there were nine referrals of individuals and 14 referrals of corporations to the DOJ in 2010 for “serious indications of violation(s)” of federal securities or other laws. A September 12, 2010 memo prepared by FCIC legal staff and sent to all of the FCIC Commissioners contains information on seven of referrals and includes some big names."

Sen. Elizabeth Warren followed up to ask why a referral to the FBI to prosecute PwC related to the AIG-Goldman Sachs conflicts, for one, never happened.

The FCIC memo notes two potential legal violations as a result of Goldman Sachs’ behavior in connection with collateral calls to American International Group Inc. for structured products that had, in Goldman’s Sachs’ view, lost significant market value. The referral memo states that, “[i]f Goldman knew it was about to lower the values of the securities it was selling ... or if Goldman had a fiduciary relationship with any of the buyers, this could represent a violation of the 1934 Act or other laws. Second, this could also be a 1933 Act violation if this information was omitted from an offering document” for the securities.

Also with regard to the AIG credit default swaps portfolio, the FCIC memo describes potential fraud by former AIG CEO Martin Sullivan and former CFO Stephen Bensinger in investor calls and by auditor PricewaterhouseCoopers as a potential “aide[r] and abettor” of fraud.

The allegations focus on a Dec. 5, 2007 investor call with CEO Sullivan when AIG reported that they were “highly confident” there would be “no realized losses” on certain credit default swap portfolios — despite the fact that the company had made “undisclosed adjustments” including a “negative basis” adjustment and a “structured mitigant” adjustment that hid losses of $5.9 billion. The FCIC investigation revealed that Sullivan, Bensinger and AIG’s auditors, PwC, were all aware of the “negative basis” adjustment prior to the December 5, 2007 call.

None of these individuals or organizations have ever been criminally prosecuted.

Nothing ever happened. Why is that?

Columbia Professor Shiva Rajgopal wrote for Forbes in defense of post-SOx financial reporting requirements.

Have Reporting Burdens Led To More Firms Staying Private?

By Shivaram Rajgopal, Forbes, Jun 08, 2025

If anything, US reporting rules need to be strengthened, not weakened. I have pointed out, time and again, the deficiencies in our financial reporting system and how auditors could potentially do a better job.

Regulators may want to proceed with caution the next time someone brings up the hypothesis that reporting burdens are a significant barrier to US firms going public.

What's next for the de-regulation crowd? Getting rid of the audit mandate.

But, be careful what you wish for.

For example, if the attorneys and their client, requesting Certiorari in the AmTrust case against BDO, are successful at the U.S. Supreme Court, they will blow up the audit mandate embedded in U.S. securities laws.

Believe me, the public company CEOs and controlling founders who invested in Theranos with no audit won’t care.

Do Investors Care At All About Audits Anymore?

Back in October I wrote here that a very long list of sophisticated investors including my ultimate boss, Rupert Murdoch of News Corp., and business partners like Walgreen’s made the decision to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in the private start-up Theranos but didn’t insist on seeing audited financial statements first. From its incorporation i…

Those attorneys and their client, BDO, will have gotten the Supreme Court to agree with their cockeyed initial defense: no one pays attention to the audit opinion, even if — prepared according to standards — it could have told investors that a company has published a materially misstated set of financial statements.

Think I am exaggerating? Why else would the Chamber of Commerce, the AICPA, and the CAQ — talk about double-teaming — have written amicus briefs in support of the request for Certiorari?

While we wait to find out if BDO can get the Supreme Court to render audit opinions meaningless, we can read about (FT.com gift link) another PCAOB enforcement action for audit professionals cheating on ethics and other training exams. This time it's the remaining three of the Big 4 in the Netherlands. KPMG had already paid a huge fine, the biggest ever imposed, for its violations.

The US audit regulator has fined the Dutch arms of Deloitte, PwC and EY a total of $8.5mn after finding “hundreds” of staff cheated on internal training exams including ethics tests, in the latest such scandal at the Big Four accounting firms. The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board said staff, partners and even some members of the firms’ senior leadership had improperly shared answers or otherwise collaborated on the tests, which are needed to satisfy internal training and professional education requirements. The enforcement actions come after KPMG Netherlands last year paid $25mn for improper answer-sharing by hundreds of staff, including its head of assurance, and for misleading regulators about the practice...

US regulators began uncovering widespread test cheating at the Big Four in 2019, but it was years before many firms implemented policies aimed at stamping out the practice, according to the PCAOB filings. It has now found instances at all of the Big Four firms and across the world, from the US to the UK and China, levying tens of millions of dollars of fines.

The non-US firms are just like US (pun intended)!

How does that happen?

Well, one way, say some researchers, is secondments.

A new research article, International Rotations in Globally Networked Public Accounting Firms: Brokering Quality Control, published in The Accounting Review by Kim Westermann of California Polytechnic State Univ. and Denise Downey of Villanova, says that secondments can "foster” audit quality.

Broadly, this study investigates how secondments are used as an interfirm brokerage mechanism to foster quality across member firms. Specifically, we focus on the role that secondments play in the GNF structure and coordinated GNF activities, such as global group audits (GGAs). Secondments are defined as international rotations of auditors from one member firm to another in a specified role for a fixed duration within the GNF network structure. To address our research objective, we interviewed 14 U.S. auditors deployed on secondment (“on tour”) from the U.S. (“U.S. secondees”), 15 non-U.S. auditors deployed on secondment to the U.S. (“non-U.S. secondees”), and 11 firm leaders. To analyze our data, we draw on the concept of network brokerage—the process of connecting actors in systems of social, economic, or political relations to facilitate access to valued resources (Kilduff and Brass 2010; Stovel, Golub, and Milgrom 2011; Stovel and Shaw 2012; Kwon, Rondi, Levin, De Massis, and Brass 2020).

Our analysis reveals that differences between member firms—or “structural holes” (Burt 1992)—continue to hamper coordinated audit work (Barrett, Cooper, and Jamal 2005). First, member firms and engagement teams may be unfamiliar with the local or international regulatory and economic environment and thus lack requisite technical knowledge. Second, geographical distance creates variations in sociocultural norms (e.g., audit practices across member firms) and language. Such challenges pose risks to individual member firms and to the firm’s global brand. Consequently, individual member firms strategically position secondees within the network as brokers to bridge the structural holes across two or more otherwise disconnected members firms.

Maybe the "network" effect of the Big 4 global networks can spread bad habits as well as bad culture. Seamless worldwide service delivery to multinationals with listings in the US necessitates Big 4 member firms in other parts of the world to maintain the required PCAOB registration and exposure to PCAOB inspections and enforcement. That's how we found out these firms were cheating.

Do you know which Big 4 firm was the first to get caught exam cheating? KPMG US, caught when the SEC was investigating its PCAOB regulatory data theft scandal in 2018-2019. KPMG, it turned out, was also cheating on remedial GAAP training exams imposed as the result of another SEC enforcement order.

Back then the SEC was driving enforcement activity for these egregious violations of the securities laws and holding individual partners accountable. The SEC later fined EY the most ever imposed on an audit firm for lying to the SEC during its investigation of its cheating scandal. But, the KPMG case was the last time any US partners were held accountable individually.

Since then the SEC has pawned these enforcement actions off on the PCAOB, who suffers the wrath of the firms and anti-regulatory crowd for highlighting how partners and firm leadership are complicit in a scam on the public.

When the Securities and Exchange Commission settled charges with KPMG LLP on June 17, 2019 for soliciting stolen regulatory data and altering past audit work, KPMG may have smarted at some of the comments from Jay Clayton and his team at the SEC:

“KPMG’s ethical failures are simply unacceptable,” said SEC Chairman Jay Clayton. “The resolution the Enforcement Division has reached holds KPMG accountable for its past failures and provides for continuing, heightened oversight to protect our markets and our investors.”

“The breadth and seriousness of the misconduct at issue here is, frankly, astonishing,” said Steven Peikin, Co-Director of the SEC’s Enforcement Division. “This settlement reflects the need to severely punish this sort of wrongdoing while putting in place measures designed to prevent its recurrence.”

“This conduct was particularly troubling because of the unique position of trust that audit professionals hold,” said Stephanie Avakian, Co-Director of the SEC’s Enforcement Division. “Investors and other market professionals rely on these gatekeepers to fulfill a critical role in our capital markets.”

The regulators may have been angry because the inadvertent discover of another test cheating scam forced Jay Clayton’s hand.

I don’t think it was planning on fining KPMG, but the unexpected discovery during the investigation of the KPMG/PCAOB “steal the exam” scandal of an even more egregious violation of public trust, and an open defiance of the SEC’s authority, was just too much.

The SEC’s settlement order said that in 2018, after the firm had discovered and announced the separation of the audit leadership professionals for the PCAOB scandal, numerous KPMG audit professionals had also cheated on internal training exams by improperly sharing answers and manipulating test results. The cheating by audit partners and personnel was on SEC-mandated re-training and testing required by an August 2017 enforcement action against the firm and one partner for audit negligence.

In addition, the SEC learned that prior to November of 2015, certain audit professionals also manually changed the scores required to pass certain exams. By changing a number in a hyperlink, audit professionals could change the score required to pass.

Five former KPMG officials and one PCAOB official were criminally charged in 2018 in the original case that alleged they schemed to interfere with the PCAOB’s ability to detect audit deficiencies at KPMG. Four eventually pleaded guilty and two were found guilty at trial.

Now three more KPMG partners have been sanctioned by the SEC for the additional test cheating scandal.

The original SEC press release and DOJ indictment for the PCAOB “steal the exam” scandal announced in January 2018 “make for some tough reading,” said John Jenkins of TheCorporateConsel.net blog.

However, Jenkins wrote on January 31, 2018, SEC Chair Jay Clayton had gone, at that time, “to great lengths to reassure the market that the scandal didn’t implicate the reliability of KPMG’s audits,” in a separate statement.

Oh, one more thing...

What ad was floating right under the FT article on the cheating scandal in the Netherlands?

Can't live with them, can't live without them.

China frauds, a 42,659 part series

WSJ Dave Michaels writes about some China scams.

Lindstrom, a college professor in Utah, invested in Jayud Global Logistics JYD 3.55%increase; green up pointing triangle, a small Chinese shipping company whose price rose for months, then crashed 96%, just after Americans like him were told to buy it. Wall Street veterans say the pattern has been repeated dozens of times in recent years, and feeds on tiny Chinese stocks that are vulnerable to manipulation and easily bought by U.S. investors.

Nearly 60 China-based companies have conducted initial public offerings on Nasdaq since 2020 that each raised $15 million or less. More than one-third have experienced sudden one-day price drops of 50% or more over the past two years, according to FactSet data. Another 17 listed companies based in Hong Kong have lost half of their market value in a single day.

The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority warned in 2022 that small IPOs involving such companies were often a prelude to fraud. Such offerings were supposed to broadly market shares to new investors. But they could instead be placed with insiders or affiliates of the company, and manipulative trading often appeared soon after the IPOs, according to Finra.

“We’re seeing this across the landscape,” said Bryan Smith, a senior vice president for complex investigations at Finra, which supervises stock brokerages.

One recent criminal case, involving China Liberal Education Holdings CLEUF -6.25%decrease; red down pointing triangle, illustrates how an alleged fraud occurs.

China Liberal, which said it ran international-study programs for Chinese college students, disclosed in December that it raised almost $21 million from 30 big investors, who agreed to purchase 160 million shares for about 13 cents each, according to securities filings.

But some of those investors were involved in a pump and dump that defrauded 600 victims, according to an indictment issued in March.

Nasdaq says it has made it harder in recent years for risky companies to remain listed on its exchange. In January, for instance, Nasdaq accelerated the process for delisting some companies whose share price falls under $1.

“Nasdaq takes its regulatory responsibilities seriously,” Nasdaq said in a statement. “Where Nasdaq does not have principal authority, such as cross-market trading activity, we proactively work with other regulators and enforcement agencies to help address instances of market manipulation.”

Authorities have recently focused on suspicious trading in the shares of several other China-based companies, including Lixiang and NetClass Technology, according to people familiar with the matter.

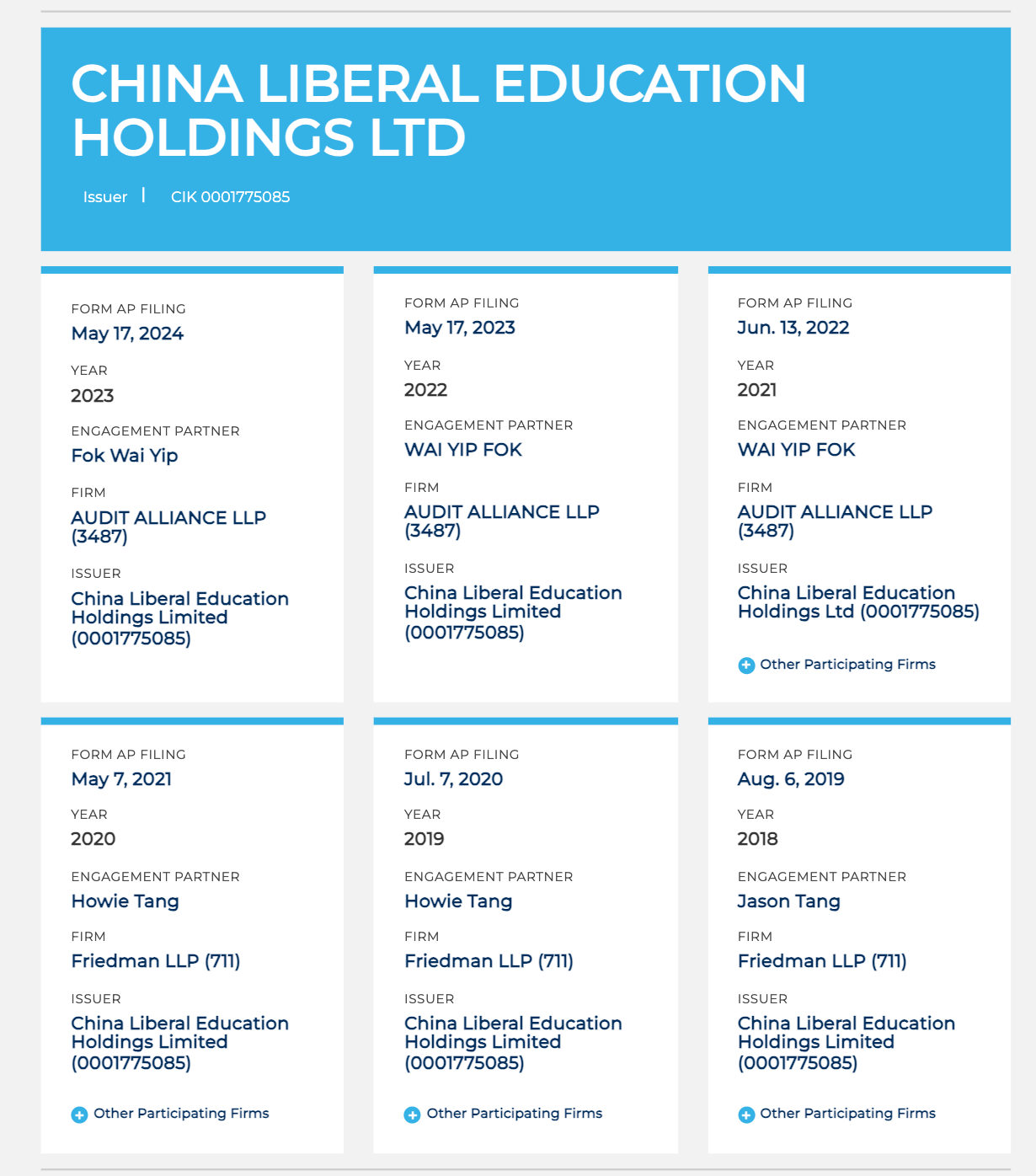

My first question to Dave Michaels was: Who audits these sketchy Chinese companies? He was on to his next investigation so I looked it up myself. (All from PCAOB's Form AP.)

China Liberal Education Holdings :

Two out of four are audited by Marcum Asia, CPAs LLP.

The other two of the four are audited by Audit Alliance out of Singapore, inherited from Friedman LLP — which was acquired by Marcum Asia affiliate firm Marcum LLP in May 2022 — and inherited from WWC, PC headquartered in San Mateo, CA, who inherited the client not long before that from PwC Zhong Tian, the Big 4's China mainland member firm.

All of these firms have had significant run-ins with the PCAOB and in one case the SEC.

Oh, and by the way... The professor from Utah featured in the story, characterized as a poor rube who "had only dabbled in investing when he was encouraged by someone impersonating a financial adviser to buy shares in a small Chinese company listed on the Nasdaq Stock Market," is no China spring chicken.

Professor Lindstrom has a PhD from University of Hawaii, Manoa, and spent two years as a visiting professor from 2022-2024 at Shanghai International Studies University. Me thinks mebbe the professor thought his language skills provided him above average insight into Chinese companies. Too bad they helped less when faced with high pressure Facebook and Instagram sales tactics.

Coincidentally, or not, since Herb Greenberg is typically on it...

Herb wrote today about how China-based Ostin Technology, a company he's written about before as too good to be true, followed the same pattern as the scams Dave Michaels wrote about.

Who audits Ostin Technology? Audit Alliance.

Looks like a tell to me.

Tomorrow, behind the paywall, I'm going to talk more about the Big 4 global audit firms and M&A, including a really interesting story about the 20+ year old merger of Bank of America and Fleet Boston. I'll also update you on Alteryx, provide some new commentary on Berkshire Hathaway, and dig into the regulatory arbitrage inherent in the Circle — and Chime— business models.

You need to be a paid subscriber for the whole shebang tomorrow.

Now's the time! Get a group together!

© Francine McKenna, The Digging Company LLC, 2025

I'm no expert in accounting and reporting requirements, but I do know something about organizations and processes. Those who think things could be restored under a Democratic administration aren't considering process and inertia. Good practices continue when there isn't enough pressure and activity to derail them. The opposite happens as well. To restart good practices takes political capital, will, and resources. The status quo is more likely, and that will mean a lack of the PCAOB, oversight, audits, or what have you will have become the norm. To regain them at that point might require an act of Congress. Good luck.