In the news: Super Micro and OpenAI

The end of October brought scary news for those invested in Super Micro and some dramatic new disclosures for those monitoring the Microsoft - OpenAI relationship.

I was coasting into the end of October, more focused on relaxing — finally — after a lot of traveling and the few trick-or-treaters in my building last Sunday.

I am always interested to see what my youngest brother dresses up as to scare the neighborhood kids.

I divide my time these days between writing this newsletter, participating in academic research projects including reading others’ works in progress and providing suggestions and commentary, guest lecturing in spots such as at Univ. of Cambridge, Stanford, Berkeley, and Univ of Miami and, occasionally, writing for others.

Quick reminder: This kind of newsletter model, which provides reliable independent journalism that operates at the intersection of professional services, business, and politics, only works if subscribers support my work with paid subscriptions. Consider upgrading by investing in The Dig.

THANK YOU for your support and encouragement and comments — I appreciate you!

But, from time to time, talking to other journalists and commenting on big news in my wheelhouse becomes all consuming. That’s what happened this past week with Super Micro, Microsoft’s new disclosures on its investment in OpenAI and, to some extent, AI in general and some other developing news I’ll write about later.

Super Micro

I talked to three journalists about EY’s very noisy resignation from SuperMicro last week and my friend and frequent collaborator Olga Usvyatsky talked to at least as many.

Brody Ford, Dana Wollman, and Nicola M. White wrote right away for Bloomberg on Wednesday, October 30, about the massive blow to Super Micro’s share price when its new auditor, EY, walked out in a huff. EY — who came on board only in March of 2023 — did not wait for an investigation of whistleblower allegations and a short seller’s report to be completed, and exited without issuing any opinions on the company’s financials.

EY stormed away and took several potshots at the company on its way out the door.

Ernst & Young raised questions about the firm’s commitment to integrity and ethics, according to a filing that Super Micro released on Wednesday. “We are resigning due to information that has recently come to our attention which has led us to no longer be able to rely on management’s and the Audit Committee’s representations,” Ernst & Young wrote.

Super Micro is under an enormous amount of scrutiny and EY maybe felt singed as the blaze in Super Micro’s kitchen became way too hot.

The resignation comes after news broke last month that the US Department of Justice had launched a probe into an ex-employee’s claims that Super Micro violated accounting rules. A month earlier, Super Micro said it would delay its annual financial filings and that a special committee was evaluating internal controls over financial reporting. The company said Wednesday it would hold a quarterly “business update” call with investors next week.

Deep Quarry’s Olga Usvyatsky was quoted by Bloomberg and her earlier report on the noisy resignation phenomenon —eerily prescient — was linked to.

This kind of public criticism by an auditor is “extremely rare and a huge red flag,” said Olga Usvyatsky, an accounting analyst. In two other high-profile auditor resignations this year — from SunPower Corp. and Tingo Group Inc. — the companies were ultimately delisted, she wrote in an analysis earlier this month.

I’ve talked to two reporters whose takes have not yet come out. But another one, Amanda Gerut at Fortune, gave me a lot of space to expand on the subject.

Accounting expert Francine McKenna told Fortune that the EY resignation went beyond the usual quiet exit auditors make when they slip away from an engagement. “There are noisy resignations and then there are resignations that bang a big giant gong—and this is as bad as it can get,” said McKenna, who authors The Dig newsletter.

In its resignation letter, EY wrote that it was no longer able to rely on management and the board’s audit committee, which is supposed to be made up of independent directors who oversee the company for the benefit of shareholders. “When you can’t rely on management, that’s bad,” said McKenna. “If you can’t trust the audit committee, there is something very wrong.”

Super Micro is supposed to provide an update on its search for a new auditor — it’s now punched the ticket for two, EY and its former auditor Deloitte who walked away quietly in March after 18 years — on November 5. Via Fortune:

Not ideal timing, given that’s Election Day. Super Micro declined to comment further.

Amy Lynch, former regulator with the SEC and Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, told Fortune it appears EY has “serious concerns about the company and contacted the SEC in order keep themselves from being charged in any subsequent enforcement action.”

“SMCI may very soon find itself under investigation by the SEC for accounting-related fraud, if not already,” said Lynch, founder and president of FrontLine Compliance. “The SEC acts very quickly in these circumstances.”

Did EY file a 10A? That’s what Ms. Lynch is implying.

Section 10A of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 requires reporting by auditors to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) when, during the course of a financial audit, an auditor detects likely illegal acts that have a material impact on the financial statements and appropriate remedial action is not being taken by management or the board of directors.

The story was too hot — the stock plunged 33% on Wednesday, and another 12% on Thursday — for Bloomberg’s Matt Levine to skip. However, I am not sure he’s got the reputational impact of such a noisy exit by an auditor right.

By the way, what are EY’s incentives here?

Resigning means it won’t get any more revenue from Super Micro, but any one audit assignment is not particularly material. The real question is whether this helps or hurts at the margin in getting other auditing business. If you are an audit firm, do you want a track record of sometimes noisily resigning in a way that leaves your clients in an embarrassing lurch? Yes, right? Not a lot, but the right amount: A reputation like “we won’t work with companies we can’t trust” makes your audits seem more trustworthy, which arguably makes you a more appealing auditor for other companies that think they are trustworthy.

It seems like it should work that way, doesn’t it? Sort of a Goldilocks and the three bears’ porridge temperature balance between too easy vs. too mean.

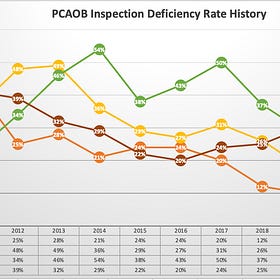

But academic research says companies actually want auditors to “go along, get along” more than anything else. For example, according to recent research on auditors’ judgments when the vast majority of companies release annual earnings before the audit is completed, I reported on at MarketWatch that…

…the practice of leaving a wide gap between an earnings release and the release of a fully audited 10-K leaves auditors in a tough spot if they find adjustments are needed. They know that the market will react negatively to a revision, particularly a downward revision, and that can make them reluctant to push for changes. That risk increases if the auditor fears losing a client or is too close to the client.

“In this situation, auditors frequently exhibit biased decision processing and lower judgment quality after adopting the client’s financial reporting goal of avoiding any adjustments,” Schroeder said last month when interviewed by MarketWatch.

Also, clients who receive adverse internal control opinions (ICOs) from auditors are more likely to dismiss those auditors and seek replacements (i.e., engage in internal control opinion shopping) (Ettredge et al. 2011; Newton et al. 2016). But it’s worse than that:

Don't Make Me Look Bad: How the Audit Market Penalizes Auditors for Doing Their Job

Elizabeth N. Cowle, Colorado State University, Fort Collins - Department of Accounting, and Stephen P. Rowe, University of Arkansas

Extant literature documents that publicly observable audit inputs (e.g., auditor size, industry specialization) and outcomes (e.g., restatements) have significant reputational effects for clients and their auditors. While these findings demonstrate situations in which auditors are incentivized to maintain their reputation for quality in order to attract future business, we posit this may not always be the case.

Our study provides empirical support suggesting that the market for audit services penalizes auditors when they do their job but communicate information to the public that is critical of management (i.e., issue adverse ICOs). We show that, on average, audit offices experience a decline in future growth following the issuance of an adverse ICO, suggesting that clients avoid auditors that have a history of disclosing items that make their clients look bad. We provide evidence which suggests that the decline in future audit office growth is a product of the auditor’s diminished ability to attract new clients and is not auditor-driven. Furthermore, we document a more pronounced decline in future growth when auditors issue adverse ICOs to more visible clients or issue adverse ICOs that refer to entity-level control weaknesses. We also provide evidence that auditors can recoup some of their losses when they change their behavior and issue fewer adverse ICOs.

In December 2021, Jean Eaglesham wrote for the WSJ about another recent paper paper that suggests there’s a signal provided to investors based on the timing of an auditor resignation:

When Companies Fire Their Auditors, Timing Is Clue to Future Trouble

Study shows that when auditors are fired late in the year, accounting problems are more likely

When a company and its auditor split up, it can be a sign of trouble in the books. But the two sides typically don’t give a reason for the breakup.

Two accounting professors instead looked at the timing of the split. They found that the later in the year it occurs, the more worried investors should be…

Companies are meant to alert investors to disputes between them and their auditors under securities rules. But firms that fire their auditors typically keep quiet about any underlying tensions, the two accounting professors found. “Neither the company nor the auditor wants to air dirty laundry by disclosing disputes. It could create legal liability and also reputational risk,” said Jeffrey Burks of the University of Notre Dame, who co-wrote the study with Jennifer Sustersic Stevens of Ohio University.

The study looked at thousands of auditor dismissals from 2000 to 2013. The professors found the risk of a future restatement or a material weakness in internal controls is higher when the firing occurs closer to the end of the year. Dismissals during the 30 days after the filing of the annual report didn’t indicate higher risk of restatements, according to the research.

When companies fire their auditor in the second half of their financial year, or after the year ends when auditors have begun their fieldwork, the chance of a future restatement is 40% higher compared with companies that haven’t switched auditors, the study found.

Soooooo, Super Micro:

Very noisy resignation, not quiet at all. Check.

Near end of year. Check, check.

Auditor cites issues not only with management “tone at the top” but with Audit Committee. Check, check, check.

Reported DOJ investigation regarding potential criminal accounting issues, whistleblower and Hindenburg Short report, sanctions issues. So many checks the company might as well have been attacked by someone with a giant Sharpie pen.

In a statement to Fortune, a Super Micro spokesman said it disagreed with EY and added it is working “diligently” to hire a new auditor. The spokesman emphasized that Super Micro does not believe it will need to issue any restatements or corrections to its financials.

Which audit firm Super Micro hires, and how long it takes to get one to take the assignment, will determine this company’s future. I would not take the promise of no restatements to the bank and try to cash that check.

OpenAI and Microsoft

There was a dramatic development in the story of the relationship between Microsoft and Open AI this past week.

Subscribers to The Dig will recall that approximately a year ago Olga Usvyatsky and I wrote that there was no evidence in Microsoft SEC filing disclosures of an equity method investment in OpenAI. That’s despite the fact that every other journalist was characterizing it as such without showing any evidence.

Almost all of the reported statements about the relationship came from OpenAI. Microsoft went along and didn’t contradict because, of course, it was in its interest to do so.

Notice how all of the "investment" activity described is inward facing. Microsoft says it will increase its investment in specialized supercomputing systems, will build out Azure infrastructure, will deploy OpenAI models in its own products, and will continue to sell Azure to OpenAI as its customer. Microsoft will integrate OpenAI technology with its new line of Microsoft’s products, and OpenAI is going to use Azure as its exclusive cloud provider.

Notably absent from Microsoft's official press release is any mention of a specific purchase of shares in OpenAI or any terms of the deal, i.e. the size of any outward-facing investment in OpenAI the company or how much, if any, of the investment came as a direct cash injection.

All of the quantitative terms of the deal — a $10 billion investment round, a 49% Microsoft ownership of OpenAI, and that a substantial portion of the investment is a long-term non-cash commitment for Azure cloud computing credits — were reported by the press, and the press alone, using the anonymous source reference of "people familiar with the matter".

Cross post: What can accounting tell us about Microsoft's partnership with OpenAI?

This is a cross post from Deep Quarry, a substack newsletter by my friend and frequent collaboration partner Olga Usvyatsky.

Not that long ago I was quoted by Alistair Barr in Business Insider regarding a very extensive discussion of OpenAI financial statements in The Information, a specialized tech publication. However, again, The Information’s transparency was less than satisfying to me.

Alistair Barr at Business Insider has written about a report from The Information about the financial statements for OpenAI that The Information has supposedly reviewed.

There is enough detail there to say they looked at something, but what?

Barr focuses on how OpenAI tries to use adjustments to tell another story about its profitability. I am quoted.

'Not kosher'

I also asked an accounting expert to go on the record about this. I chatted with Francine McKenna, who writes The Dig, a blog focusing on accounting, audit, and corporate-governance issues at public and pre-IPO companies. She used to work at KPMG Consulting and PwC, and implemented accounting and financial systems, including SAP and Oracle ERP software, for big companies.

She knows accounting and technology well. She read The Information story closely on Thursday and had this to say about OpenAI's efforts to get investors to ignore the cost of training its AI models.

"That is a bridge too far," McKenna told me. "It's not kosher."

For an AI company like OpenAI, training models will be an ongoing process. The world is constantly evolving, and new data is being generated, which will have to be incorporated into AI models' understanding.

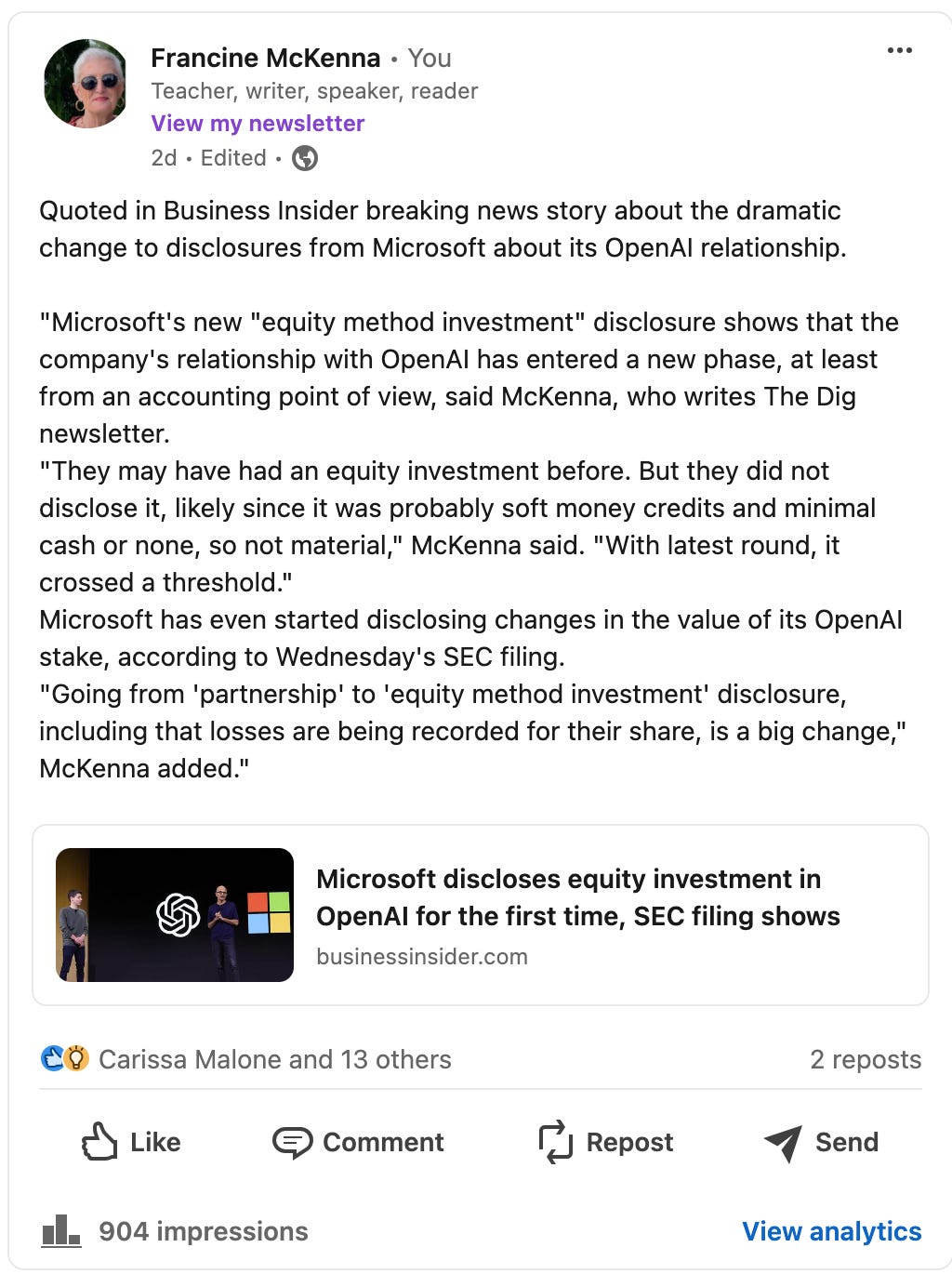

Well, now we finally have some disclosure from Microsoft.

Ashley Stewart at Business Insider caught the change in Microsoft’s latest 10-Q:

The accounting expert Francine McKenna told Business Insider that the new disclosure suggested all or part of Microsoft's previous investments in OpenAI were "soft money," such as discounts or credits for services and internal spending that fell below a certain threshold where the software giant didn't need to publicly disclose details.

A Microsoft spokesperson said on Wednesday that its partnership with and investments in OpenAI hadn't changed.

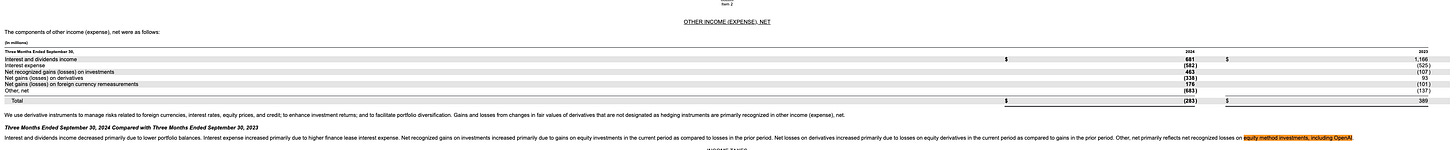

As you can see Microsoft is still being cagey. In the 10-Q just filed for the 1st Quarter of fiscal 2025, ending Sept. 30, 2024, Microsoft mentions OpenAI 6 times. It uses the phrase “equity method investments, including OpenAI,” 3 times. For the first time Microsoft tells us that its equity method investments, other, which includes OpenAI, sent $683 million of losses to Microsoft in the first quarter ending September 30, 2024, of fiscal 2025.

By comparison, in Microsoft’s 10-K for the fiscal year ending June 30, filed July 30, 2024, OpenAI is mentioned 9 times, but primarily in service to demonstrating Microsoft’s commitment to exploiting the AI market. In other words, name drops for hype purposes.

Open AI is characterized as a “strategic partnership,” only, twice.

In January 2023 we announced the third phase of our OpenAI strategic partnership.

This AI may be developed by Microsoft or others, including our strategic partner, OpenAI. We expect these elements of our business to grow.

We envision a future in which AI operating in devices, applications, and the cloud helps our customers be more productive in their work and personal lives. As with many innovations, AI presents risks and challenges that could affect its adoption, and therefore our business. AI algorithms or training methodologies may be flawed. Datasets may be overbroad, insufficient, or contain biased information.

The phrase “equity method investments, including OpenAI,” does not appear at all in the June 30, 2024 10-K.

I’d say the Microsoft-OpenAI relationship has reached a dramatic new stage, one that is now quantitatively, or at least qualitatively, material enough to require more extensive disclosure.

© Francine McKenna, The Digging Company LLC, 2024