Is the SEC finally going after non-GAAP revenue adjustments?

The example of Square says not totally, and that's maybe because some are pushing for one aspect of the problem to go away by changing the rules entirely

On June 13, 2019, the Audit Committee at Square approved, effective immediately, the engagement of Ernst & Young LLP as the Company’s independent registered public accounting firm for the Company’s fiscal years ending December 31, 2019 and December 31, 2020. EY replaced KPMG, who had been Square’s auditor since at least 2011.

Square’s announcement of the auditor change, noted, as is typical, that neither Square nor anyone acting on behalf of Square, had consulted with EY prior to the appointment regarding:

the application of accounting principles to a specific transaction, either completed or proposed, or the type of audit opinion that might be rendered on the Company’s consolidated financial statements, and neither a written report nor oral advice was provided to the Company that EY concluded was an important factor considered by the Company in reaching a decision as to any accounting, auditing, or financial reporting issue,

any matter that was subject of a disagreement within the meaning of Item 304(a)(1)(iv) of Regulation S-K, or

any “reportable event” within the meaning of Item 304(a)(1)(v) of Regulation S-K.

Regulation S-K is the part of the US Securities Act of 1933 that lays out reporting requirements for various SEC filings used by public companies.

Companies make this disclosure about consulting with a new auditor before they are on the job because getting their take on the company’s accounting and disclosure beforehand might be construed as “auditor opinion shopping.” Opinion shopping is a perennial topic of discussion, one that’s been around for as long as I have been on the job.

“It has been the subject of SAS 50 and SEC reporting release FRR 31. It has been discussed in SEC enforcement releases, AAERs 14, 32, 54, and 220 and was considered by the Treadway Commission. It has been a factor in several alleged audit failures.”

Opinion shopping is when a company looks for an auditor that’s willing to support a proposed accounting treatment that will help a company achieve its reporting objectives even though the proposed approach is controversial, dubious or on the margin of acceptable treatment given current standards. But the company is set on a particular approach because it improves reported operating results or the company’s financial condition, and so it looks for a firm and set of partners who can “make it work.”

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, passed in response to major corporate financial scandals such as Enron and WorldCom, didn’t stop opinion shopping according to research published in the May 2019 issue of the American Accounting Association quarterly Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory. The academics reported that most companies in its study sample engaged in auditor opinion-shopping and the practice paid off in a reduced likelihood of receiving going-concern opinions, even as it increased financial misstatements.

“Successor auditors are incentivized to keep their new clients until they recover start-up costs and are thus more susceptible to client pressure,” the professors wrote. Incumbent auditors, by the time they are dumped, have recovered some or all of their client start-up costs.

What was Square potentially opinion shopping about when it decided to switch to EY from KPMG?

I wrote about it in January 2020:

On Nov. 6, 2019 Square announced in an SEC filing that it was making a change to its accounting after receiving an SEC comment letter.

The company said it would no longer report adjusted revenue, a non-GAAP metric.

Square had been using the metric to adjust gross revenue to net by subtracting transaction-based costs and bitcoin costs. But the company also was adding back deferred revenue that had been permanently written off after acquisitions, an issue I wrote about at MarketWatch.com multiple times.

In an FAQ about the change, Square said that it started using the metric in November 2015, “to provide investors and analysts with useful metrics to measure the performance and growth of our ongoing recurring business and allow comparability to other businesses in the payment processing sector.”

It will now “discontinue the use of the adjusted revenue measure based on the SEC’s evolving position with respect to non-GAAP performance measures,” the FAQ said.

Only 3 letters discussing the issue went back and forth between the SEC and Square, although there are indications there may have been several phone calls and at least one live meeting between them. The full duration of the review, 16 months, was certainly much longer than average. The process may have been delayed because, along the way, Square changed auditors, from KPMG to EY and changed CFOs.

I reported another strange thing about the correspondence between the SEC and Square. The lead engagement partner for KPMG LLP, Charles Lynch, had been copied on the first two responses Square made to the SEC’s comment letters. Then two EY partners, Dave Cabral and Hal Berliner, were copied on the last letter on November 18, 2019 after EY had been appointed auditor.

I wrote in January how rare it was to see a company’s audit partners copied on correspondence between the company and the SEC about its accounting. It doesn’t happen often because it publicly suggests the auditor is advocating for its client’s position with the SEC and is, therefore, not independent.

Staff Statement on Management's Report on Internal Control Over Financial Reporting, May 16, 2005

The Commission’s auditor independence requirements with respect to services provided by auditors are largely predicated on four basic principles. [That is, 1) An auditor cannot function in the role of management, 2) an auditor cannot audit his or her own work, 3) an auditor cannot serve in an advocacy role for his or her client and 4) an auditor and audit client cannot have a relationship that creates a mutual or conflicting interest.]

In addition to these four basic principles, the Commission’s rules also specifically identified nine categories of prohibited services. The auditor’s discussing and exchanging views with management does not in itself violate the independence principles, nor does it fall into one of those nine prohibited categories of services. The staff supports a strong audit profession where a hallmark of its professionalism is to exercise sound judgment in both the audit and in ongoing dialogue with management [emphasis added]. The staff recognizes that questions arise in certain circumstances as to the proper application of accounting standards. Investors benefit when auditors and management engage in dialogue, including regarding new accounting standards and the appropriate accounting treatment for complex or unusual transactions. The staff believes that as long as management, and not the auditor, makes the final determination as to the accounting used, including determination of estimates and assumptions, and the auditor does not design or implement accounting policies, such auditor involvement is appropriate and is not of itself indicative of a deficiency in the registrant’s internal control over financial reporting.

Why would a company like Square copy its current auditor and then its incoming auditor?

A University of Texas accounting Ph.D. candidate’s draft research paper, co-authored by an associate professor there, describes the advantages of copying the audit partner on comment letters. Short answer: Companies that copy the auditor when responding to the SEC, pay higher fees, but the total resolution time is shorter when a more experienced auditor is copied, measured by the number of years of auditor experience.

EY had signed as auditor mid-year 2019, in June 2019, and delivered its first audit opinion for Square eight months later on February 26, 2020.

Who now leads the Square audit for EY? One of the EY guys who was copied on the company’s response to the SEC on the ongoing issue, Dave Cabral.

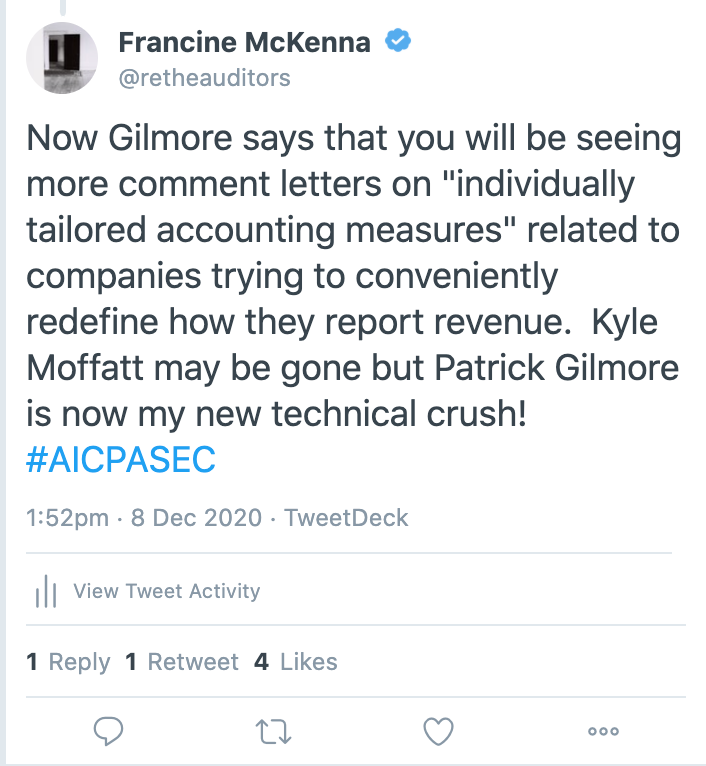

As Square’s FAQ stated, the SEC’s position with respect to non-GAAP performance measures is “evolving.” I wrote in my last piece for MarketWatch in November 2019, that the SEC was finally showing signs of cracking down on some especially abusive non-GAAP metrics that adjusted revenue, or in SEC-speak, substituted “individually tailored recognition and measurement methods for those of GAAP.”

With my colleagues Ciara Linnane and Katie Marriner, I analyzed comment letters issued by the SEC in 2018 and 2019 that had revenue-related non-GAAP keywords. Often clients were simply being advised on how to handle new revenue-recognition rules that came into effect in January of 2018. But some were also being advised on their accounting related to adjusted revenue and, in particular, “acquisition-related” adjustments for deferred revenue that had been written off under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, or GAAP, the U.S. accounting standard.

As first reported by MarketWatch in November of 2017, companies are adding back millions in this written-off deferred revenue, or “ghost revenue,” when reporting adjusted revenue and when calculating executive bonuses.

MarketWatch has reported on the use of the “ghost revenue” by NortonLifeLock formerly known as Symantec, and by BlackBerry, Salesforce, Broadcom and others.

Read: Companies including Symantec are using ‘ghost revenue’ to calculate bonuses

Still, there are clear examples that the SEC’s interaction by comment letter has led to changes in reporting on revenue adjustments.

For instance, the SEC questioned software company Ribbon Communications in a letter in April of this year about its “acquisition-related revenue” adjustment.

“Considering your deferred revenue was adjusted to fair value at the time of acquisition pursuant to GAAP, please tell us how you considered whether your various non-GAAP measures that include this adjustment are substituting an individually tailored recognition and measurement method for a GAAP measure,” the letter said.

The SEC forbids “individually tailored recognition and measurement” methods because they substitute the company’s own interpretation of accounting standards for GAAP.

Ribbon Communications agreed in a response to the SEC in June to remove the metric from future filings.

Also in April, the SEC took exception to a related adjustment to revenue by BlackRock, Inc. BLK, 0.73%, the world’s biggest asset manager. BlackRock was using a non-GAAP adjustment to deduct distribution and servicing costs before arriving at an adjusted revenue metric that it then used to calculate an adjusted operating margin.

“Based on the information provided, we believe your adjustment for distribution and servicing costs in the computation of “revenue used for operating margin measurement” substitutes an individually tailored recognition and measurement method for those of GAAP, which could violate Rule 100(b) of Regulation G,” the SEC wrote.

The SEC told the company not to disclose the metric in future filings.

But like a lot of accounting and audit regulatory and enforcement activity at Jay Clayton’s SEC, this effort was inconsistent and scattershot.

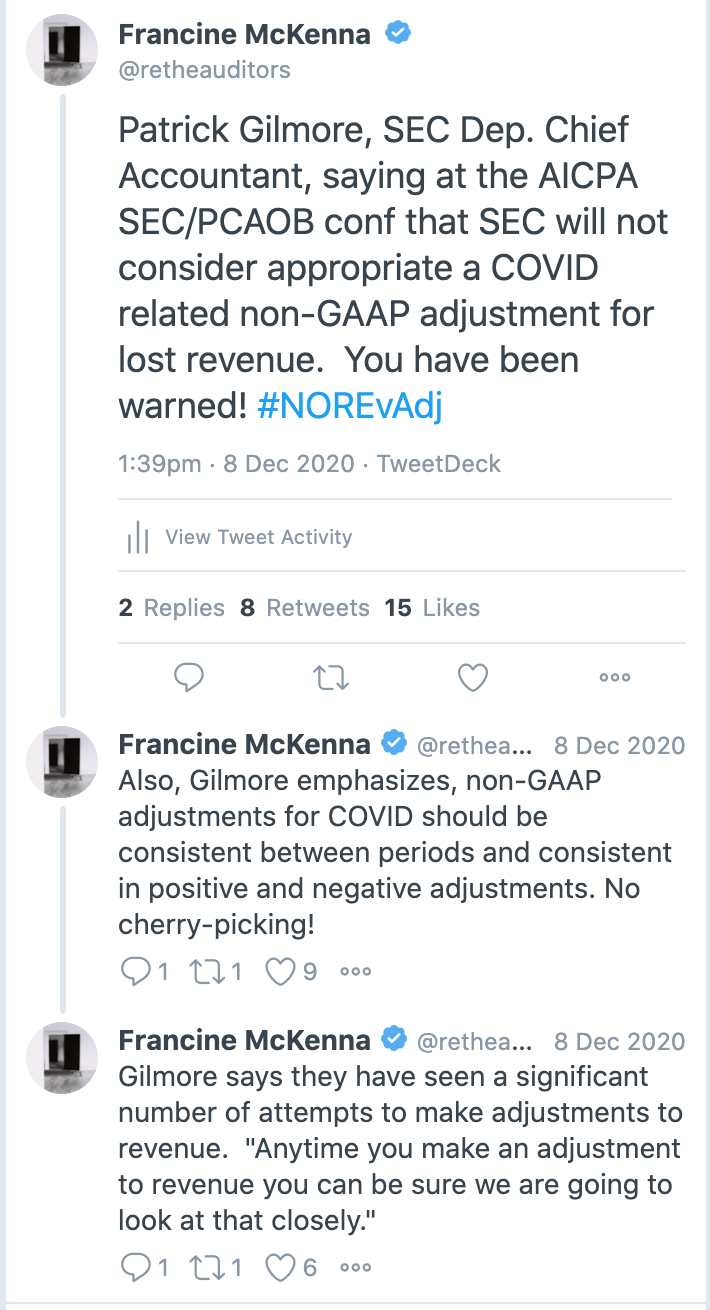

So it was heartwarming to hear an SEC official say “game on” again in December of 2020.

Does this mean the SEC is finally going to crack down on “ghost revenue” non-GAAP adjustments?

Not exactly.

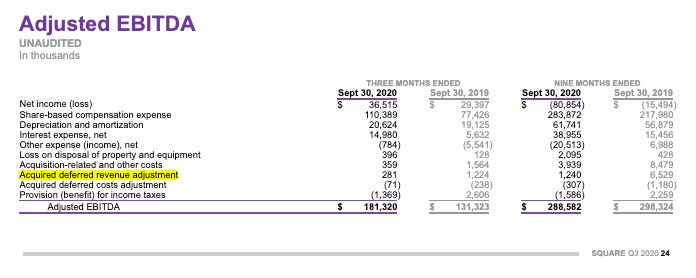

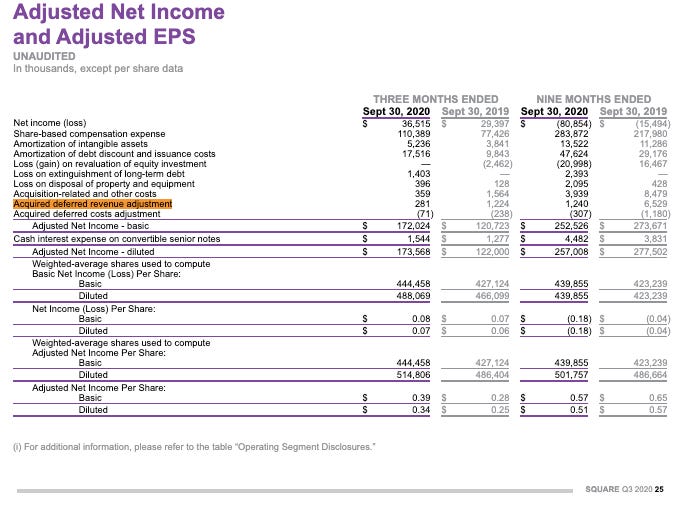

Just look at Square. The company is still adding back its “ghost revenue” — acquired deferred revenue that was written off permanently when the acquisition occurred — to its Adjusted EBITDA, Adjusted Net Income, and Adjusted EPS non-GAAP metrics. Here’s the most recent summary of the impact of this adjustment from its latest earnings release:

In my next newsletter, available only to paid subscribers, I will explain how FASB plans to fix the “ghost revenue” problem. It seems to be following Jay Clayton’s lead. When Clayton’s SEC was faced with rules no one wanted it to enforce, it simply reversed them.

© Francine McKenna, The Digging Company LLC, 2020

If you are not yet a paid subscriber, please consider signing up to receive all the newsletters, including the ones with original information and analysis for active investors.