Part 2: What is KPMG's bank audit quality history with the PCAOB and SEC?

KPMG has a long history of criminally poor ethics and lousy bank audit quality, but the DOJ, SEC, and PCAOB, just like the FRB and DFPI, keep giving KPMG a break.

In Part 1, I provided background about how, in March 2023, three banks audited by KPMG failed in quick succession and another previous KPMG audit client, Credit Suisse, was forcibly acquired by UBS.

In Part 1 I also described media coverage initially focused on the lack of going concern warnings and critical audit matters, or CAMs, from KPMG that are relevant to the causes of the failures that are being discussed. My opinion is that coverage was a distraction.

I covered the issues identified in reports from the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank (including public disclosure of all prior supervisory materials) on April 28 and by the California DFPI on May 8. These reports summarize FRBSF and CDFPI’s supervision of Silicon Valley Bank and review the circumstances believed to have led to the failure of the bank. On May 11 the US General Accounting Office, or GAO, also issued a report that incorporates comments on Signature Bank, the next one to fail after SVB, as well as SVB. (I will introduce the GAO report here in Part 2.)

Finally, I matched the issues identified by the regulators to the auditing standards (GAAS) issued by the audit regulator, the PCAOB, to see whether KPMG should have potentially mentioned any of these issues in their audit opinions, possibly as material weaknesses in internal control over financial reporting, or ICFR.

The primary issues identified by FRBSF and CA DFPIof interest to us with regard to KPMG are:

Corporate Governance and Risk Management (Control Environment/Tone at the Top in the PCAOB standards)

Internal Audit

Managing liquidity/solvency, interest rate risk and technology in a changing economic and regulatory environment (Planning the Audit: Awareness of the Company's Economic, Regulatory and Business Environments in the PCAOB standards)

I will attempt to answer this question today in Part 2:

What is KPMG's history with the PCAOB and SEC regarding bank audit quality control?

Coming up in Part 3, I will attempt to answer these remaining questions:

Why should we look at KPMG's history as auditor of Credit Suisse?

Why don't auditors enthusiastically report material weaknesses in internal control over financial reporting on a timely basis?

How might KPMG auditor independence issues and conflicts as a result of the revolving door between the firm and the banks have affected its objectivity and willingness to act to warn investors, and the market, of issues at the banks?

Does KPMG now operate with impunity and little accountability after two near-deaths in the U.S. alone since 2005?

In Part 3, I will also wrap up a discussion of additional media coverage of other issues such as bank incentive compensation, the revolving door between KPMG and the banks, the impact of crypto customers on these banks.

What is KPMG's history with the PCAOB and SEC regarding bank audit quality control?

To complete the discussion of auditing standards from Part 1, in Part 2 I will provide some history of KPMG's interactions with the PCAOB and tie the PCAOB GAAS standards to the PCAOB's previous inspections of KPMG. The purpose is to understand how auditors are expected to address these issues in their reports and whether KPMG has had trouble doing that in the past.

Where was KPMG while Silicon Valley Bank, and the rest, were teetering?

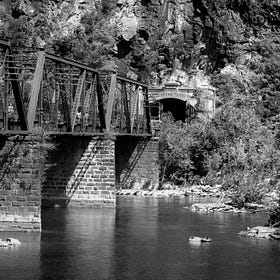

When Silicon Valley Bank was teetering — in March 2023 the very large "regional" bank was obliterated after a massive deposit run in the space of a week — I thought about writing about how its external auditor, KPMG, is the #1 auditor to banks. I waited instead and was rewarded with not one, not two, but three banks audited by KPMG that went under in short order and another PacWest, that is still going but too much in the news for wrong reasons. (Photo by Francine McKenna at Harpers Ferry, VA)

The KPMG-PCAOB Scandal

On April 11, 2017, KPMG announced that six employees would leave the firm, including the head of its audit practice in the United States Scott Marcello and David Middendorf, the national managing partner for audit quality and professional practice. In February 2017, an internal whistleblower, a veteran KPMG partner, had informed KPMG’s leadership of an information “leakage” between the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board’s, PCAOB, and KPMG’s national office.

The firm learned in late February, from the internal source, that an individual who had joined KPMG from the PCAOB subsequently received confidential information from a then-employee of the PCAOB, and shared that information with other KPMG personnel. That information potentially undermined the integrity of the regulatory process.

(Sounds a lot like the PwC Australia confidential government tax info case in the news now, doesn’t it?)

KPMG immediately reported the situation to the PCAOB and the SEC, and retained outside counsel to investigate. KPMG learned through the investigation that the six KPMG individuals had either improper advance warnings of engagements to be inspected by the PCAOB, or were aware that others had received such advance warnings and had failed to properly report the situation in a timely manner.

“This issue does not impact any of the firm’s audit opinions or any client’s financial statements,” KPMG said in its statement, which has now disappeared from its website after a restructuring.

KPMG's assertion that the "leak" did not affect its audit opinions nor its clients’ financial statements was an attempt to reduce the impact of the scandal by convincing clients, regulators, and the public that illegal and unethical behavior of individual partners, even its most senior audit practice partners in its National Office, did not affect KPMG’s overall audit quality. KPMG’s effort was also, likely, an attempt to convince the PCAOB that “tone at the top” weaknesses cited in its 2015 inspection report and Part II quality control findings, at that time not yet available to the public, had been remediated. Leaders KPMG had deemed responsible, including the firm’s Chief Auditor, had been terminated.[1]

The 2017 audit inspection scandal involved the theft of confidential regulatory information by KPMG and PCAOB personnel that is critical to the PCAOB core mission of ensuring audit quality for U.S. listed companies. The scandal implicated several high-ranking partners at KPMG, including its Audit Quality and Professional Practice, National Managing Partner of Audit Operations, Chief Auditor, and Inspections Leader. They had all used illegally obtained PCAOB information to falsely improve the results of KPMG’s PCAOB audit inspections.

The seriousness of the scandal was confirmed by the criminal prosecutions of KPMG and PCAOB executives, leading to several guilty pleas, a public trial with two guilty verdicts, and prison terms for three individuals. The SEC also took civil action against KPMG and PCAOB personnel, and against KPMG (the firm) itself.[2]

The illegal acts began after KPMG resisted acknowledging and meaningfully correcting issues raised by the PCAOB, including poor “tone at the top”.[3]KPMG partners' plans to commit illegal acts can be traced back to December 2014, when the PCAOB met with KPMG's leadership and expressed concerns about the firms audit engagement inspection results and its lack of responsiveness to the PCAOB’s ongoing comments, particularly for its banking audit clients. The PCAOB's Part II criticisms of its 2015 KPMG inspection covering the 2014 audit period and KPMG's response were not released to the public until after the scandal and resulting enforcement actions and criminal trial concluded, in 2019.[4] It encompassed violations of law, auditing standards, and ethical standards and a rare criticism of the “tone at the top” for a Big Four audit firm.

There are no other cases of explicit “tone at the top” criticisms from the PCAOB against a Big 4 audit firm. Despite these severe early criticisms, several leaders at KPMG decided to engage in a criminal scheme, instead of quality improvement, to beat back the PCAOB's scrutiny.

Nearly a year after KPMG disclosed the partners' regulatory data theft and their separation from the firm, SEC Chairman Jay Clayton reiterated KPMG's earlier contention that the issues did not impact any of the firm’s audit opinions or any client’s financial statements. On January 22, 2018, in Clayton's statement corresponding to the announcement of the SEC and DOJ charges against the KPMG and PCAOB individuals, Clayton advised KPMG clients, investors, and the markets that he did not believe the charges against the six individuals would “adversely affect the ability of SEC registrants to continue to use audit reports issued by KPMG in filings with the Commission or for investors to rely upon those required reports.” Clayton also reassured investors and the markets that he did not expect the indictments to cause interruptions in the “orderly flow of financial information to investors and the U.S. capital markets, including the filing of audited financial statements with the Commission”.

My initial impression was that the SEC was following an informal "too few to fail" policy to avoid contributing to a crisis of client and investor confidence at a Big 4 audit firm, and potentially driving KPMG to Arthur Andersen's post-Enron fate. In retrospect, Clayton's reassurances may have been prompted by banking regulators worried about systemic risk for all of KPMG's bank clients — which include systemically important banks Citigroup and Wells Fargo, and included at the time Deutsche Bank and Credit Suisse, if the SEC disclosed concerns about KPMG's audit quality. The FT reported:

Banking clients are particularly significant to KPMG. Publicly listed banks paid the firm more than $325mn in fees in 2021, the last year for which full data is available, with the sector accounting for about 14 per cent of KPMG’s fees from public clients. That compared to 8 per cent at PwC, 3 per cent at EY and 2 per cent at Deloitte.

Clayton also said, in his January 2018 statement, that he had asked PCAOB Chairman Bill Duhnke to review a prior assessment of the regulator's internal information technology and security control weaknesses to assess how the theft of confidential regulatory information had continued for three years and to take further action, if necessary.

There has never been a public "root and branch" report provided to the public by the PCAOB or SEC of the issues identified and remedial actions taken, including separations of professionals from the agency, by the PCAOB.

The origins of the KPMG-PCAOB scandal are found in KPMG’s poor performance in the PCAOB’s inspections of its 2012 to 2014 audits. During those years, KPMG’s auditing deficiency rates increased more than its peers, reaching their highest levels in 2014, when the PCAOB judged 54% of inspected KPMG audits as deficient.

In response to the increasing pressure from the PCAOB, KPMG sought to improve its performance by:

Developing multiple internal monitoring programs including one specifically aimed at loan and lease losses at its banking clients;

Increasing National Office personnel primarily by hiring inspection professionals from the PCAOB;

Assigning National Office staff, including former PCAOB staff, to coach audit teams whose engagements to subject to PCAOB inspection;

Revising audit team incentives from a punitive model for inspection deficiencies to a reward system for clean PCAOB inspections; and

Hiring data analytics consulting firm Palantir to develop a predictive model of engagements likely to be targeted by the PCAOB.

In May 2015, Brian Sweet, a former PCAOB inspector with expertise in financial institutions, joined KPMG as a partner. He immediately shared the names of engagements the PCAOB planned to inspect in 2015 with leaders of KPMG’s national office (i.e., David Middendorf, Thomas Whittle). This information was received after most of the clients on the list had already issued annual reports that included KPMG’s audit opinion, and thus the underlying workpapers were locked from further changes. Sweet also shared additional confidential information with Palantir to improve the predictive modeling of engagement selection. Under the provisions of Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the PCAOB’s Ethics Code, Rule EC9, both actions were clearly illegal.

In 2016, Sweet again provided the list of banking clients targeted for PCAOB inspection to several KPMG leaders.[5] The timing of this information was critical. Because the 2016 inspection information was provided to KPMG during the 45-day documentation period, KPMG engagement teams had time to alter engagement workpapers for issues they anticipated the PCAOB would review, before the audit workpapers were locked but, in most cases, after the audit opinion had been issued.

During this time, Sweet and another former PCAOB executive, Cynthia Holder, were working closely with engagement teams focusing particularly on clients that were part of KPMG’s allowance for loan losses, or ALL, monitoring program. In his trial testimony, Whittle noted that “[i]n 2016 all 10 issuer banks inspected participated in the monitoring program and received no comments in our historical areas of deficiencies in testing complex aspects of the allowance.” After the 2016 inspection cycle, KPMG leaders met with the PCAOB and noted the significant reductions in deficiencies, not mentioning that the improvements were enabled by KPMG's illegal advance notice of which engagements would be inspected.

In February 2017, Sweet again illegally obtained a list of engagements targeted for inspection by the PCAOB and informed KPMG leadership. It is important to note the timing of this transmission. This information was received while audits were still being completed, so KPMG engagement teams had an opportunity to alter audit testing and documentation “in-flight,” that is before the audit was completed, before the audit opinion was issued, and before the workpapers were locked from further changes.

The KPMG-PCAOB scandal presented an opportunity to review whether a significant shock, one that led to the termination and in some cases criminal prosecution of KPMG’s US audit practice leadership, was associated with a change in the audit quality of the firm.

Based on the recent failures of KPMG audited banks I would assert that the 2017-2018 scandal shock did not lead to an improvement in KPMG’s audit or auditor quality. I say this because:

KPMG didn't highlight entity-level control environment and "tone at the top" issues identified by the FRBSF and CDFPI at any of the banks that recently failed.

KPMG did not, in my opinion, perform the audits according to auditing standards that require its planning to include a full assessment and understanding of changes in the banks' business environment, regulatory environment, business models, risk profiles, customer profiles, asset and liability growth trends, and economic and interest rate changes and does not appear to have expanded its scope and testing as a result of these changes.

KPMG did not include in its opinions or communications with investors any acknowledgement of serious regulatory concerns that suggested looming liquidity and solvency issues or issues related to risk management and internal audit at the banks and KPMG did not recognize any of these issues as material weaknesses in internal control over financial reporting in their opinions at any of the banks.

KPMG did not reflect any subsequent issues that came to its attention after year-end and before the audit opinions were signed at SVB on Feb. 24, 2023, at Signature Bank on March 1, and at First Republic Bank on February 28.