The PCAOB wants to get tough with the auditors

This not our first time at this rodeo. It will end in tears. Again.

On July 25, 2023, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, the U.S. audit regulator, released a report that previewed the results of its 2022 inspections of the audits of the 2021 financial statements of U.S. listed companies.

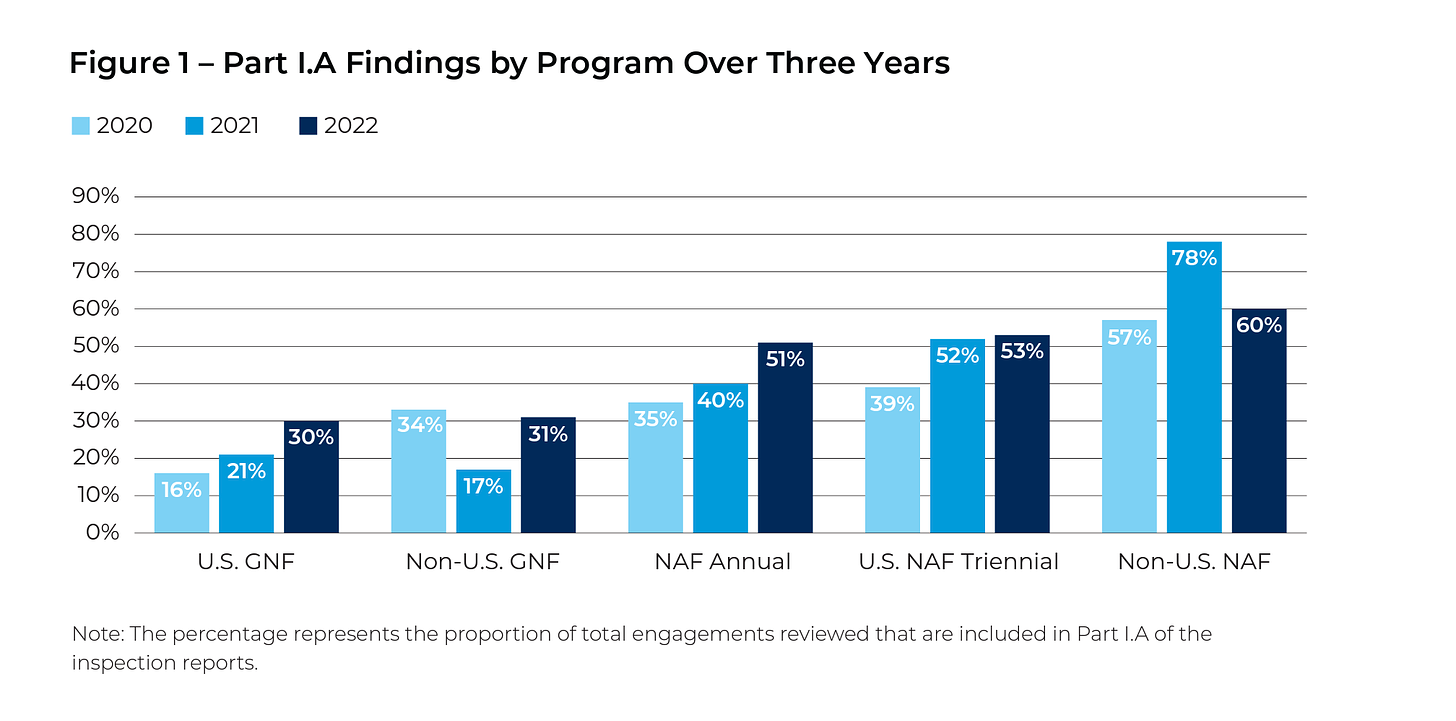

The “Staff Update and Preview of 2022 Inspection Observations(PDF)” presents only summary-level observations, for now, from the PCAOB’s inspections of selected public company audits performed by 157 audit firms in 2022. The report says that approximately 40% of the audits reviewed will have one or more Part I.A deficiencies, deficiencies that will be included in the individual audit firm inspection reports.

That's up from 34% in 2021 and 29% in 2020.

The PCAOB said that the most significant increase in 2022 was observed within the Global Network Firms (GNF) category of firms, the largest global firms in the U.S. and outside the U.S. like Deloitte, EY, KPMG and PwC, that are inspected annually by the PCAOB.

Part I.A of the individual audit firm’s inspection report discusses deficiencies, if any, that were of such significance that PCAOB staff believes the audit firm, at the time it issued its audit report(s), had not obtained sufficient appropriate audit evidence to support its opinion on the public company’s financial statements and/or internal control over financial reporting.

In other words, the auditor should not have provided an audit opinion.

We do not yet have the reports on individual firms, such as the largest global network firms — Deloitte, EY, KPMG, and PwC. A PCAOB spokesperson told me that the Global Network Firms (GNF) reports would be issued "as soon as possible this year. One of PCAOB’s our strategic goals is the timely issuance of inspection reports, which is why this preview spotlight was issued several months earlier than in previous years."

The July 25 preview report confirms what PCAOB Chair Erica Y. Williams warned about in December 2022. That’s when the PCAOB provided a preview of its 2021 inspections of audits of public company 2020 financial statements.

“Higher deficiency rates in 2021, coupled with the fact that the PCAOB is also seeing an increase in comment forms for 2022, are a warning signal that the audit profession needs to sharpen its focus on improving audit quality and protecting investors. The PCAOB will continue our work to increase audit quality by modernizing our standards, enhancing our inspections, and strengthening our enforcement.”

The “Staff Update and Preview of 2021 Inspection Observations(PDF)” report also showed a year-over-year increase in the number of audits with Part I.A deficiencies. Here's a chart from the 2022 report that breaks it down by the type of audit firm, whether it is U.S. or non-U.S. firm, and by inspection frequency.[1]

The PCAOB also expects that approximately 46% of the audits reviewed will have one or more Part I.B deficiencies, up from 40% in 2021 and 26% in 2020. Part I.B deficiencies cover noncompliance with PCAOB standards or rules such as critical audit matters or CAMs, Form AP which identifies the engagement partner and participating audit firms, and certain auditor independence related deficiencies.

On July 25, 2023, Chair Williams used her bully pulpit once again to bemoan the miserable inspection results, results which are supposed to be a proxy for the state of audit quality.

“These findings are absolutely unacceptable, and audit firms must make changes to turn things around and live up to their responsibility to investors. The PCAOB will continue demanding firms do better, conducting transparent inspections, and bringing strong enforcement actions where appropriate. We are also asking audit committees to hold firms accountable by posing tough questions to their auditors on behalf of investors.”

The PCAOB and audit quality

When the PCAOB was created by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in 2002, Congress responded to relative perceptions of what the U.S. financial system needed at the time not to organic market forces.[2] Some believed the SOX law was passed primarily to assuage popular outrage over Enron and the myriad accounting scandals at the time such as WorldCom, Health South, Tyco, and others. It would, therefore, be a structurally weak law.[3]

The PCAOB was designed to address the market failure of Enron by legislators, regulators at the SEC, and the formerly self-regulated U.S. audit industry who, in some cases, reluctantly agreed to its provisions. The implosion of Enron’s auditor Arthur Andersen resulted from a perceived lack of audit quality and auditor independence.

The PCAOB has been trying to define audit quality, and has been playing whack-a-mole on auditor independence, ever since.

The primary stated goal of the PCAOB's inspection program is to "drive improvement in the quality of audit services" but improving audit quality remains one of its most elusive goals.[4] There has never been a consensus for how the PCAOB should promote and measure audit quality or what investors and markets would consider sufficient audit quality. As a result, the various stakeholders talk past each other using varied, conflicting, and often vague definitions of audit quality.

For example, I see chronic conflation in academic and regulatory discussions of issuer financial reporting quality metrics such as restatements and audit firm and audit process quality metrics such as audit hours and partner time.

The Standing Advisory Group of the PCAOB first discussed the necessity of a Quality Control Standard at its inaugural meeting on June 21-22 of 2004, nineteen years ago. An audit quality control standard has still not been adopted.

As a result, the PCAOB is vulnerable to constant criticism for doing things that don't improve "audit quality" as defined by investors, for example, or achieving an acceptable consistent level of it. That leads to repeated, and lately more frequent, eruptions of investor and market disappointment.

That, in turn, has led to more, and more effective, litigation against auditors.

It has also led to more negative media coverage for the industry. [5] As a result we have a chronic, and growing, disconnect (and gap) between the level of issuer financial reporting quality investors expect from companies when the auditor issues a "clean" audit and the level of financial statement quality — especially with regard to warnings about fraud and potential insolvency.

PCAOB chairs and SEC Chief Accountants go on periodic reform rants warning the audit profession to "sharpen its focus on improving audit quality and protecting investors,” and promising to "continue our work to increase audit quality". They occasionally promise to crack down on firms and individual auditors via disciplinary and enforcement activities.

But the disappointment, or “expectations gap” between what auditors say they are required to deliver when under scrutiny and what everyone else expects from audits leads to a recurring debate about the need for the PCAOB. That debate has been politically tainted by polarized views about the efficacy of more or less regulation ever since the idea of an independent regulator was first floated.

I find the need for an independent audit regulator hard to argue with and have written so many times.

However, the ongoing lack of effectiveness of the PCAOB, as it is structured and operating in reality, is now making it tough for me to keep making that case.

It doesn't help that the PCAOB has been fighting a formidable opponent since the beginning. The largest audit firms and "bought and paid for" industry and legislative supporters have resisted the PCAOB’s authority since its inception. They have even openly embarrassed the regulator by publicly dismissing its findings about audit quality and the firms’ quality control systems.[6]

After the KPMG/PCAOB scandal — where one GNF audit firm was so persistently resistant to the regulator that it decided to subvert the PCAOB's regulatory mission by stealing the list of its audit clients who would be inspected for three years — the PCAOB now gives audit firms, investors, and public companies a heads-up on what areas of the audit inspectors will be placing a greater emphasis on during its upcoming inspection cycle.

CPA Practice Advisor, July 5, 2022

As shown in the most recent batch of audit inspection reports for 2020 that the PCAOB released last November, the Big Four firms have started paying attention to what the regulator has included in its cheat sheet. PwC had an all-time low Big Four audit deficiency rate of 1.9% (one audit botched out of 52 inspected), while Deloitte, EY, and KPMG made less errors than the previous year’s inspections.

I suspect the PCAOB lately feels it has to constantly prove its value to avoid being suddenly shut down by the SEC or legislation or a court decision.

For example, in anticipation of the PCAOB's inspection access, finally, to Chinese audit firms, someone repeatedly leaked the names of the companies whose audits would be inspected to major media. The leaker's goal, I guess, was to reassure politicians and industry critics that even the limited initial reviews of only two firms in Hong Kong were going to cover some big names with big market capitalization.

No one but me blinked.

The PCAOB goes to China, well, just Hong Kong and inspects some audits

On December 15, 2022 the PCAOB announced that more than 30 PCAOB staff members had conducted a total of eight on-site inspections and additional investigations in Hong Kong of two Big 4 global network member firms: KPMG Huazhen LLP of mainland China and PricewaterhouseCoopers of Hong Kong.

The WSJ reported a “scoop” on Sept 15 that, "The U.S. accounting inspectors are expected to review the audit work papers of multiple companies including Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., Yum China Holdings Inc., NetEase Inc. and JD.com Inc." citing anonymous sources. Back in September, and again in August, Reuters also reported a “scoop” of the names of client engagements that were expected to be inspected, based on leaks from more than one anonymous source, cited as “the people” who told Reuters, the declined to be identified due to confidentiality constraints. Maybe also because it is illegal to leak confidential inspection data?

These leaks are the same actions by someone(s) that resulted in six criminal prosecutions and guilty pleas or verdicts including jail sentences. Is it ok for, I assume, someone at the PCAOB or SEC to leak info to reassure investors and markets but when an audit firm seeks advance knowledge its professionals get criminally prosecuted?

Recall it was theft of the lists of the engagements to be inspected from the PCAOB that resulted in four KPMG audit partners, one KPMG executive and one PCAOB official being charged criminally and either pleading guilty or being convicted at trial. Two were sentenced to jail terms.