The WSJ's Dave Michaels on the SEC's inscrutable write-offs

Dave Michaels files before the New Year rings in and it's a humdinger! In the future when you see those big headlines about SEC record fines, maybe you'll be a bit more skeptical.

Hail, Caesar, those who are about to die salute thee. Suetonius

The Wall Street Journal's Dave Michaels worked late New Year's Eve, and filed a really interesting story about the SEC at 9:00 pm. Lots of people are writing about the Trump administration transition and what to expect from proposed SEC Chair Paul Atkins on enforcement, crypto, and every other niche issue that is important to their business and bottom line.

This story is, instead, a bread and butter story, one that took a long time to come to fruition and, to some extent, ignores politics. It's more about tradition, and status quo, and the hidden bureaucratic machinery under the headlines.

It was a highly promoted story by the WSJ, on page 1 on New Year's Day — overshadowed by the tragedy in New Orleans — and promoted on all the social media platforms.

SEC Writes Off $10 Billion in Fines It Can’t Collect

Internal data shows securities enforcers bring in far less money than their cases indicate By Dave Michaels Dec. 31, 2024 9:00 pm ET

There's got to be a name brand hook for a story this wonky, especially in the DC bureau WSJ where big layoffs in February of last year were ostensibly intended to refocus reporters on getting more scoops, especially about politics and to push financial and regulatory reporting to New York, and not spending time doing regulation-related stories that take years to see the light.

From Semafor:

WSJ bleeds talent: The Wall Street Journal laid off a list of well-regarded Washington reporters in early February, then rushed to assure three of them — Pulitzer winner Brody Mullins, Ted Mann of Bridgegate fame, and the political money sleuth Julie Bykowicz — that they would be able to apply for new jobs. It appeared to be an attempt to get around union rules requiring layoffs be structured by seniority, but it backfired badly: Morale at the Journal appears to be back in the toilet. Adding insult to injury, all the reporters the Journal sought to retain will instead take their union-mandated severance.

Fortunately, Dave Michaels survived those cuts but many of our fellow WSJ DC softball team buddies like Brody, Ted and Andrew Ackerman did not. Brody is fine — he's got a great book out — Ted is at Bloomberg, and Andrew is now at the Washington Post. (Despite my boast of being a Southside Chicago 16 inch softball pro, I should have hung my spikes up a long time ago. But the guys were always good sports and, every once and a while, I hit in the clutch.)

Dave Michaels uses the funny story of Paul Bilzerian to draw you in at the lede.

Paul Bilzerian has been on the run from the Securities and Exchange Commission for so long that he now owes the agency $180 million with interest—almost three times what a court initially ordered him to pay.

For 31 years, the agency has tried and failed to collect a $62 million judgment against the former corporate raider for securities fraud. To avoid paying the penalty, Bilzerian pleaded poverty and twice declared bankruptcy. He later moved to the island nation of St. Kitts and Nevis, beyond the reach of the U.S. government.

The financier told The Wall Street Journal in 2014 that he “would rather starve to death than earn a dollar to feed myself and pay the government a penny of it.” So far, he has mostly succeeded.

I knew this story and many others like it because Dave and I had been talking about this phenomenon for a while. In particular, we’ve talked about how the SEC often publicized large fines and penalties that were never going to be collected by the SEC, itself. Sometimes, like Bilzerian, when the SEC did have claim to the penalties they were never collected at all.

While I was shooting ideas and examples at him he was diligently filing FOIAs. The FOIAs turned out to be not entirely helpful but, as a result, illuminating. From Michaels’ WSJ article:

The case is emblematic of the commission’s long struggle to enforce its judgments against individuals who go to great lengths to avoid paying them. And in other circumstances, the SEC publicizes penalties that it will never collect because defendants can receive waivers if they make payments in related criminal or overseas cases. Those two dynamics mean the SEC typically brings in less money than is apparent.

In 2023, the commission touted court orders or settlements representing $4.9 billion in financial sanctions. But it also wrote off $1.4 billion in penalties levied in prior years, according to data obtained by the Journal.

I recently wrote about Cloopen, a Chinese issuer that had been promoted at the recent Securities Enforcement Forum in DC as a model of cooperation. That's because its lawyers negotiated no penalty despite Section 10b and Rule 10b(5) scienter accounting fraud allegations.

So did Cloopen deserve no penalty for its collusive, executive level fraud? Maybe it's easier to slap a bunch of folks on the hand for Section 10b and Rule 10b(5) accounting fraud. The company got rid of bad guys and did the SEC’s work collecting clawbacks. But it’s not so easy for the SEC to collect penalties from Chinese companies based in the Cayman Islands. Maybe it's not worth the trouble to ask.

I certainly can't get anyone to tell me if the SEC ever collected anything from Luckin, the Chinese coffee company that went out in a spectacular fraud a few years ago.

There was a strange offset provision in the SEC's settlement based on the outcome of the Luckin Cayman's liquidation that also required approval from Chinese government.

The SEC's complaint, filed today in the Southern District of New York, charges Luckin with violating the antifraud provisions of Section 17(a) of the Securities Act of 1933 and Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and Rule 10b-5 thereunder. The complaint also alleges that Luckin violated the reporting, books and records, and internal control provisions of Sections 13(a) and 13(b)(2) of the Exchange Act, and Rules 12b-20 and 13a-16 thereunder.

Without admitting or denying the allegations, Luckin has agreed to a settlement, subject to court approval, that includes permanent injunctions and the payment of a $180 million penalty. This payment may be offset by certain payments Luckin makes to its security holders in connection with its provisional liquidation proceeding in the Cayman Islands. The transfer of funds to the security holders will be subject to approval by Chinese authorities.

However, Cloopen did agree to pay US $12,000,000 in cash to settle State and Federal Actions related to its IPO. So, the money was there for some industrious U.S. lawyers.

What Dave was most interested in the whole time, I think, was to nail down a write-off number. Basically he wanted to know how much the SEC gave up on versus what it took credit for in press releases. Despite many different FOIA responses and detailed analysis of SEC reported numbers for fines/penalties, Accounts Receivable, Reserves for Bad Debt, and Collections, that was much more difficult than it should have been. Here's Dave Michaels explaining why, in a supplemental post on LinkedIn.

You may notice that the first bullet mentions me as a source who tried to help Dave pin down the write-off number. Notwithstanding the fact that it is highly unusual for a major journalist to publish "highlights, including a couple from my notebook that didn't make the cut," I am grateful for the shout-out. Other than Hester Peirce, there were few other commenters besides those related to companies or individuals he mentioned.

What did Commissioner Peirce say? From Michaels’ WSJ article:

“If we are going to advertise the numbers that we are imposing, we ought to be transparent about the fact that does not mean that money is flowing to the government and to investors,” said Commissioner Hester Peirce, a Republican member of the SEC.

Yeah, have to agree there.

So what's going on? Why was it difficult to reconcile all the numbers the SEC provided via FOIA and that were published in its annual reports? Dave Michaels did eventually come up with a number. From Michaels’ WSJ article:

Over the past 10 years, the SEC has written off almost $10 billion in penalties, according to the data, which the Journal obtained under the Freedom of Information Act.

One complicating factor is that the SEC follows a Treasury rule that requires it to write-off balances that are uncollectible after two years.

But that does not mean collections have to stop.

As Dave wrote on LinkedIn:

📓 The SEC continues trying to collect some penalties that are written off, but it doesn't disclose much about which cases these are or how much success it has. (Some can be run down via court records.) This converts these penalties to an "off the books" asset, as my former colleague Francine McKenna explained to me.

My comment on the LinkedIn post was:

As I mentioned, Dave Michaels has been thinking about this issue for a long time and we’ve been putting our heads together on it almost as long. The story linked below is one of his from 2019. From Michaels’ WSJ article:

While the SEC previously shared how much of its enforcement bounty actually got collected, it stopped doing so in 2019, and declined to say why.

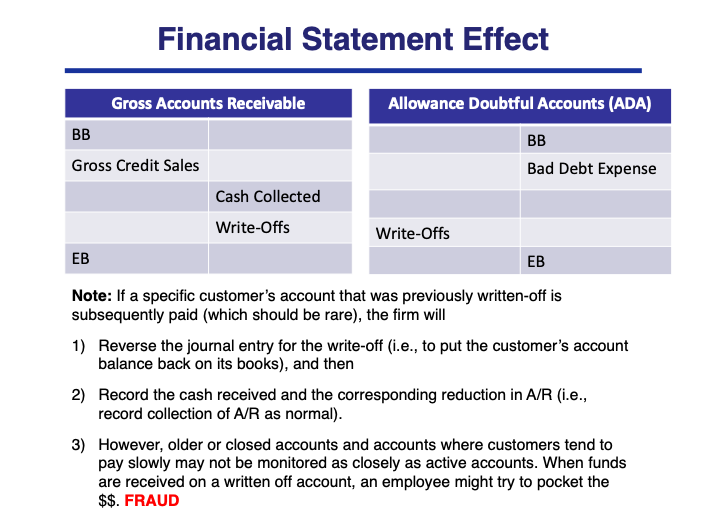

If we go back to basic accounting for receivables, allowance for bad debts, and write-offs, we can see that the quick write-off — relatively speaking for the SEC, but slow for a regular company — coupled with ongoing collection efforts and commingling of published financial statement numbers and off the books numbers presents a really big challenge for anyone trying to track the collections efforts and the write-off activity from the outside without going to the trouble of FOIAing for years. That’s because the ongoing collections efforts are apparently an "off the books" exercise.

I gave Dave the formulas so he could try to derive the write-off numbers based on the info he had. In the end it did not work cleanly because the collections information he received had a mix of "on the books" and "off the books" activity.

In the past the SEC has been under pressure to show that it was punishing the bad guys. From Dave Michaels’ WSJ article:

The SEC has faced political pressure since the 2008-09 financial crisis to extract higher penalties, according to James Park, a law professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, who researches the agency’s work.

But the political winds have changed. Attorney Cydney Posner for Cooley LLP:

According to Politico, Atkins was a “noted skeptic” of Dodd-Frank. In testimony before Congress, the WSJ reports, he took the position that Dodd-Frank “invested too much authority in regulators to decide how to restrain risk-taking at big banks.” Politico observes that he “has argued that corporate penalties harm both shareholders and employees.”

The WSJ reports that, in 2006, “Atkins supported a set of SEC guidelines that suggested sparing use of penalties against public companies. He favors suing individual wrongdoers instead, arguing that forcing companies to pay fines hurts shareholders.” Politico quotes a former regulator and colleague, who said that Atkins “‘genuinely loves this shit….He loves thinking about it. He loves talking about it.’”

That's not a great approach, according to those who study it with data, but logic does not seem to be getting in the way of the incoming administration. Maybe we'll have an SEC fines/penalties jubilee under Atkins.

I am sure he would be hailed like Caesar.

© Francine McKenna, The Digging Company LLC, 2025

The issue here is judicial accounts receivable vs financial statement accounts receivable. SEC fines are like IRS tax accounts receivable. It sits there with the potential to be collected but for accounting reasons does not show up in the financial statements.

The statement that bothered me the most was the one on stating the annual write-off is hard to find. That points to a failure in FASAB standards. It should be clear from reading the financial statements.

The IRS also collects judicial accounts receivable. I wonder if they do a better job the SEC. Perhaps the government should centralize debt collection regardless of source. The Bureau of the Fiscal Service already does this for some debts.