Uber and Lyft settle with New York but there's so much more to the story

We think everyone missed the real story of the Uber/Lyft settlement with New York. And Uber took advantage of so many legal fracases to pull another stunt.

I like writing about Uber and Lyft. The ongoing saga of their “innovative” business model, and the “innovative” accounting that accommodates it, provides me with more fodder for analysis than I can keep up with.

First, some background

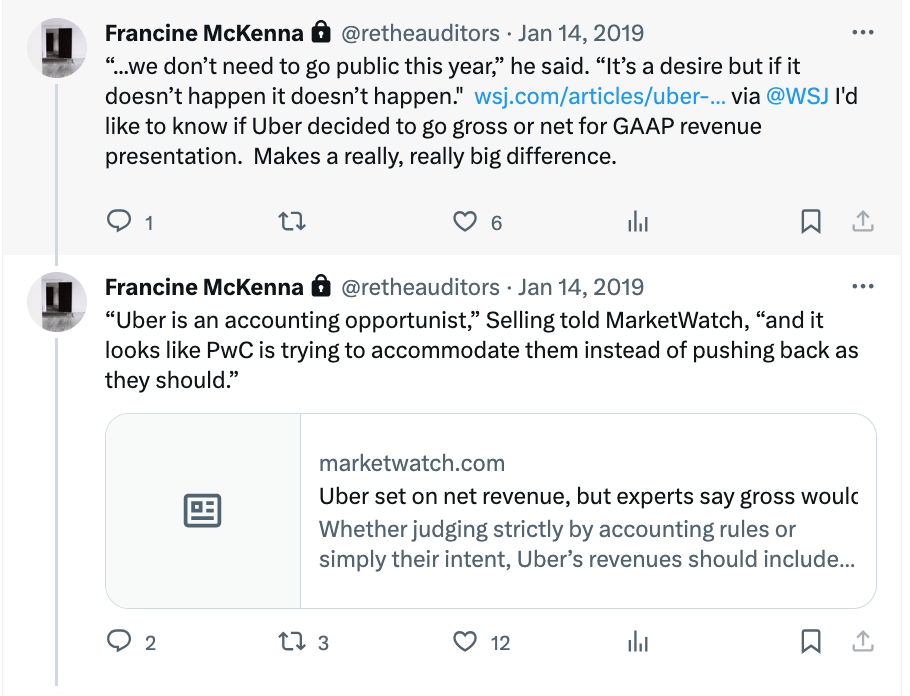

Early on, media reporting of pre-IPO Uber and Lyft irked me. The WSJ and others would dutifully report unaudited numbers full of alternative metrics dictated directly by company executives.

At MarketWatch we had tried to counter that programming.

As we got closer to the IPO, it got tougher to counter the hype.

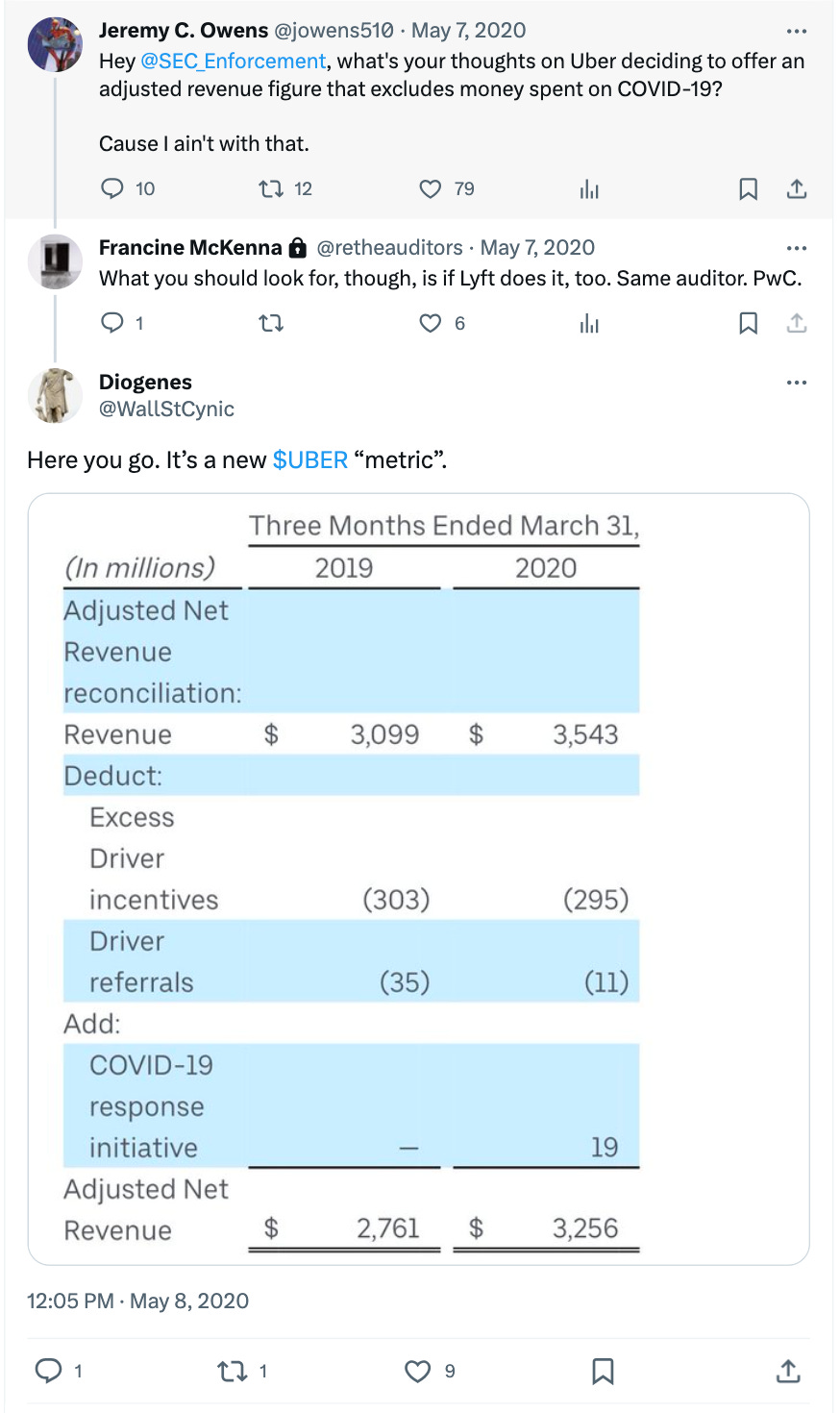

When the companies went public, the accounting nonsense continued. How many times can you say the word “adjusted”? By the way, revenue is never supposed to be adjusted!

What even is an “excess driver incentive”?

From the Uber 10-Q for the 1Q of 2020.

“Excess Driver incentives are primarily related to our Rides products in emerging markets and our Eats offering.”

Tell me more.

Adjusted Net Revenue

We define Adjusted Net Revenue as revenue (i) less excess Driver incentives, (ii) less Driver referrals and (iii) the addition of our COVID-19 response initiative related to payments for financial assistance to Drivers personally impacted by COVID-19. We define Rides Adjusted Net Revenue as Rides revenue (i) less excess Driver incentives, (ii) less Driver referrals and (iii) the addition of our COVID-19 response initiative related to payments for financial assistance to Drivers personally impacted by COVID-19.

We define Eats Adjusted Net Revenue as Eats revenue (i) less excess Driver incentives, (ii) less Driver referrals and (iii) the addition of our COVID-19 response initiative related to payments for financial assistance to Drivers personally impacted by COVID-19.

Excess Driver Incentives

Excess Driver incentives refer to cumulative payments, including incentives but excluding Driver referrals, to Drivers that exceed the cumulative revenue that we recognize from Drivers with no future guarantee of additional revenue. Cumulative payments to Drivers could exceed cumulative revenue from Drivers in transactions where the Drivers are our customer, as a result of Driver incentives or when the amount paid to Drivers for a Trip exceeds the fare charged to the consumer. Further, cumulative payments to Drivers for Eats deliveries historically have exceeded the cumulative delivery fees paid by consumers. Excess Driver incentives are recorded in cost of revenue, exclusive of depreciation and amortization.

I wrote about the strange revenue math for Uber in one emerging market, Brazil.

Uber customers paid more than $6 billion in cash last year, and accounting for it isn’t easy

Published: Aug. 19, 2019 at 7:46 a.m. ET By Francine McKenna

13% of money paid for rides and deliveries came as cash in 2018, which Uber admits can be a risky business

That risk still exists although the percentage has gone down, maybe because the bookings in other key markets — “In 2022, we derived 22% of our Mobility Gross Bookings from five metropolitan areas—Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York City in the United States, Sao Paulo in Brazil, and London in the United Kingdom” — have gone up.

In certain jurisdictions, we allow consumers to pay for rides and meal or grocery deliveries using cash, which raises numerous regulatory, operational, and safety concerns. If we do not successfully manage those concerns, we could become subject to adverse regulatory actions and suffer reputational harm or other adverse financial and accounting consequences.

In certain jurisdictions, including India, Brazil, and Mexico, as well as certain other countries in Latin America, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, we allow consumers to use cash to pay Drivers the entire fare of rides and cost of meal deliveries (including our service fee from such rides and meal or grocery deliveries). In 2022, cash-paid trips accounted for approximately 6% of our global Gross Bookings. This percentage may increase in the future, particularly in the markets in which Careem operates.

The use of cash in connection with our technology raises numerous regulatory, operational, and safety concerns. For example, many jurisdictions have specific regulations regarding the use of cash for ridesharing and certain jurisdictions prohibit the use of cash for ridesharing. Failure to comply with these regulations could result in the imposition of significant fines and penalties and could result in a regulator requiring that we suspend operations in those jurisdictions. In addition to these regulatory concerns, the use of cash with our Mobility products and Delivery offering can increase safety and security risks for Drivers and riders, including potential robbery, assault, violent or fatal attacks, and other criminal acts. In certain jurisdictions such as Brazil, serious safety incidents resulting in robberies and violent, fatal attacks on Drivers while using our platform have been reported. If we are not able to adequately address any of these concerns, we could suffer significant reputational harm, which could adversely impact our business.

In addition, establishing the proper infrastructure to ensure that we receive the correct service fee on cash trips is complex, and has in the past meant and may continue to mean that we cannot collect the entire service fee for certain of our cash-based trips. We have created systems for Drivers to collect and deposit the cash received for cash-based trips and deliveries, as well as systems for us to collect, deposit, and properly account for the cash received, some of which are not always effective, convenient, or widely-adopted by Drivers. Creating, maintaining, and improving these systems requires significant effort and resources, and we cannot guarantee these systems will be effective in collecting amounts due to us. Further, operating a business that uses cash raises compliance risks with respect to a variety of rules and regulations, including anti-money laundering laws. If Drivers fail to pay us under the terms of our agreements or if our collection systems fail, we may be adversely affected by both the inability to collect amounts due and the cost of enforcing the terms of our contracts, including litigation. Such collection failure and enforcement costs, along with any costs associated with a failure to comply with applicable rules and regulations, could, in the aggregate, impact our financial performance.

The tax exposure from allowing cash is big. Brazil is one of Uber’s major tax exposure jurisdictions, the others being the U.S., Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. Uber recently had to pay back VAT tax in UK, a transaction that gave rise to the some unusual accounting treatment because the company just can’t swallow the defeat. And now there’s a tax dispute in Brazil:

In May 2023, we received an assessment for 2019 and 2020 Driver social security contributions from the Brazilian Federal Revenue Bureau (“FRB”). We are contesting the assessment and we filed our administrative appeal with the FRB in June 2023. A negative decision can be appealed at multiple levels. Our chances of success on the merits are still uncertain and any reasonably possible loss or range of loss cannot be estimated.

PwC Audits Uber and Lyft

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Uber/Lyft saga is the fact that they are both audited by PwC, out of its San Francisco office. That’s going to make for some very tough juggling when Uber inevitably makes a bid for Lyft. And it is inevitable.

Just look at the numbers, as Calcbench as laid out.

At first glance, Uber dwarfs Lyft in almost every way. Most notably, Uber had roughly nine times the revenue as Lyft ($9.3 billion versus $1.16 billion) and almost the same multiple on total assets ($35.95 billion versus $4.48 billion). Uber also had a positive number for net income ($219 million) which is more than we can say for Lyft (net loss of $12.1 million).

More than that, Uber also dwarfs Lyft on several non-GAAP metrics too.

It will be hard to deny that Uber had a great opportunity to peek under the hood and make the best bid, given the proximity of Lyft’s numbers, warts and all. It’s happened before, say academics.

Francine McKenna, When Acquirer and Target in M&A Talks Share an Auditor, Purchase Price Can Suffer, Market Watch, May 19, 2015 (describing findings from Shared Auditors in Mergers and Acquisitions).

Francine McKenna, Tesla’s Musk may have to justify SolarCity deal in court, Market Watch, June 23, 2016, (describing findings from Shared Auditors in Mergers and Acquisitions).

Francine McKenna, Accounting Rule Change May Lead Time Warner to Bring Billions Mode to AT&T Deal, Market Watch, Nov 8, 2016 (describing findings from Shared Auditors in Mergers and Acquisitions).

And now about those legal contingencies

Olga Usvyatsky and I have updated our analysis of the Uber and Lyft settlement with the State of New York now that their 3Q results are out.

Contrary to popular reporting, it was really a win, for both companies, in more ways than one.

While the Attorney General’s press release provides an upbeat picture of the benefits to the drivers, Benjamin Black of Deutsche Bank described the New York Attorney General’s settlement as “a nice regulatory win” for Uber.

Notably absent from the Attorney General's statement is any directive to reclassify drivers from independent contractors to employees, a change that would significantly impact both Uber’s and Lyft's business models.

Uber’s earnings release clarified the situation, stating that the agreement with the New York AG establishes new protections and benefits while affirming drivers' status as independent contractors. This settlement indicates that the matter of employment classification is deemed resolved (emphasis added):

We also write:

The disclosure is notable for several reasons. First, as Francine McKenna noted in Market Watch article, the dispute underscores the connection between the legal position, business model, and accounting. Changes in drivers’ classification in the UK led to changes in business model, to the dispute related to VAT assessment, and to a corresponding choice response by selecting an accounting method that mitigated the impact.

Second, it manifests a reversal of Uber’s position, disclosed until Q1 2023, that the company cannot estimate losses.

Not only do Uber and Lyft now have a template for fighting employee designations in other key battlegrounds, but Uber took advantage of the chaos to book another strange litigation result.

In addition to these settlements, Uber faced a VAT-related assessment of $622 million imposed by the UK Tax Authority, consisting of $487 and $135 million imposed in June and September of 2023, respectively. Uber disclosed that the aggregate $622 million payment is currently recorded as receivable, because they are expecting a full refund when Uber wins the appeal.

That is really odd, and in my personal opinion very aggressive.

Read more about it at Deep Quarry, Olga Usvyatsky’s newsletter about SEC comment letters. We are going to be writing more together and separately about these issues in the future.

© Francine McKenna, The Digging Company LLC, 2023

If you are not yet a paid subscriber, please consider signing up to receive all the newsletters, including the ones with original information and analysis for active investors.